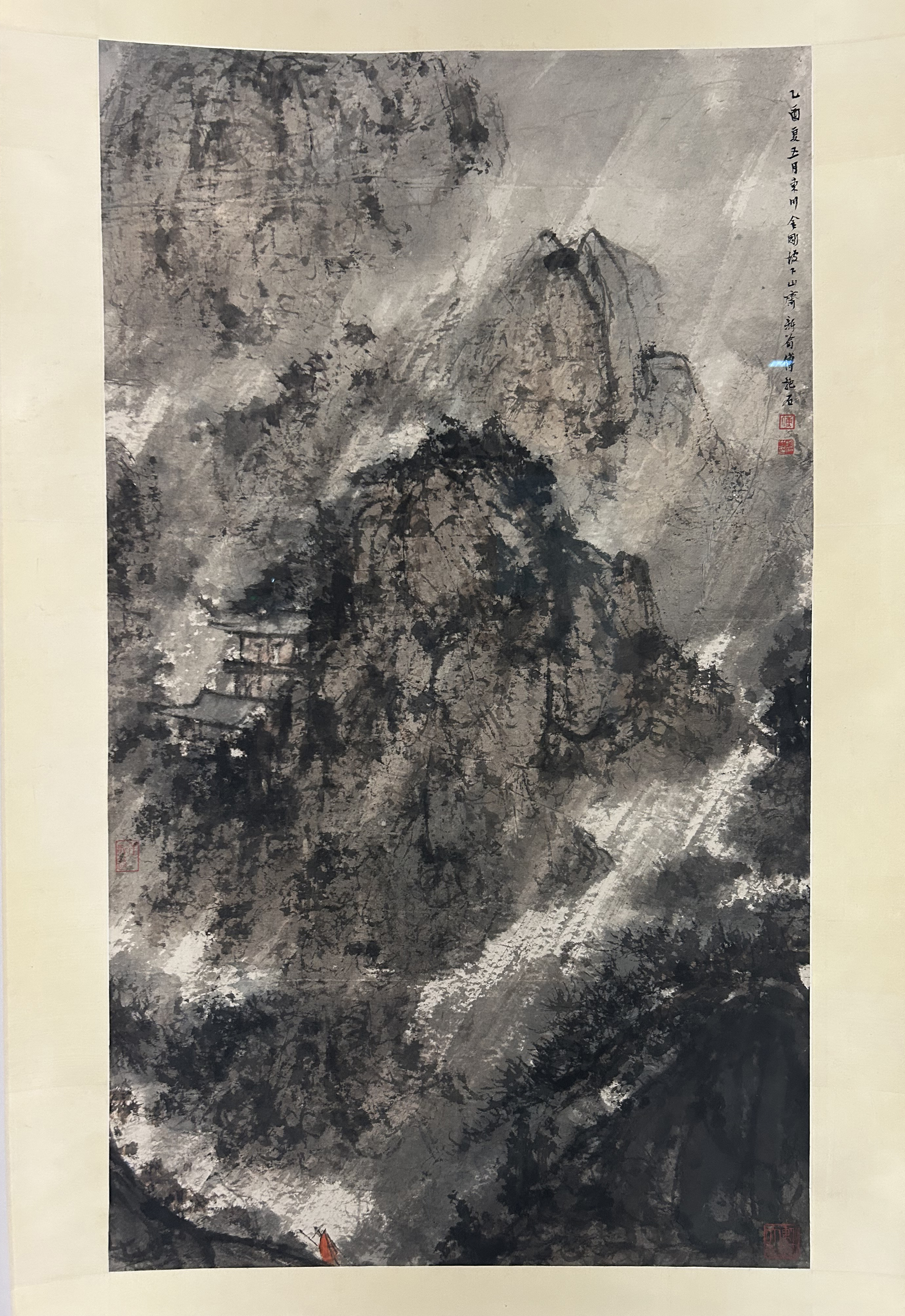

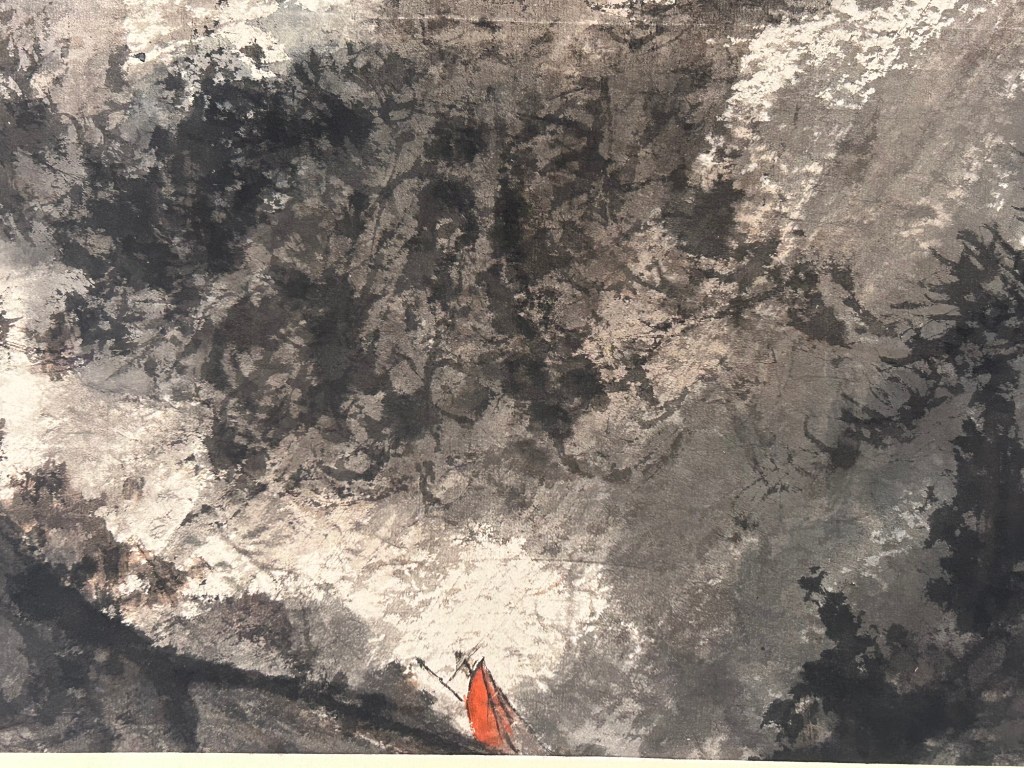

A tiny figure cloaked in red, walking staff in hand, stands head down against the rain. He wears a wide-brimmed straw hat that protects his head but exposes the nape of his neck. A torrent of summer rain washes over him and the dark path before him. It sweeps against the mountain peaks, the lush green-grey vegetation, a three-storey pavilion. The rainstorm merges the picture (the representation) with water-washed paper surface (the medium). One becomes the other. In this way the figure’s journey remains circumspectly within pictorial space, then swells out, transgressing the picture’s boundaries, expanding towards the beholder.

So, we are, and we are not, on that journey with the lone figure. He battles the water and mud on his own in the semi-darkness. But his space is our space. We move through it together. Though he may be unaware of our presence, we are fellow travelers.

The artist Fu Baoshi painted this picture on a June day in his studio at the foot of the Diamond Cliff mountains in western Sichuan province. The summer season is steamy hot and rainstorms not uncommon. That particular year, 1945, the driving rain was accompanied by bombing campaigns of the Japanese imperial army (Chongqing, the wartime capital in Sichuan, was the most heavily bombed city in the world before the Blitz). In nearby Hunan province, the Chinese military and US Airforce defeated the Japanese in the “Battle of West Hunan,” and successfully prevented Japan from seizing airfields and railway lines. But it was at a high cost; over 36,000 Chinese soldiers were killed or wounded. And the violence and the war in China continued.

Grief at human loss is a subject Fu returned to often throughout his life––during the wartime years, when he witnessed deaths caused by war, and one of his own children passed away, and afterwards, when his sadness became more muted, and his disappointments with his own life more acute. There’s an authenticity to the emotional affect of this body of work. When it is put next to the paintings he made for the state (paintings that were commissioned by Chairman Mao, for instance) the difference in Fu’s engagement of his mind and brush is stunning. His pictorial renditions of Mao’s poems are flat, perfunctory, literal, often washed in red. They are far from poetic. But it is in this––the more private, the more intimate paintings (even if large scale)––where we can sense the shadowy presence of the artist, the figure beyond the painted figure.

So, there’s a paradox, and it is evident in this picture. Grief is an intensely personal emotion. It sets you on a path that you have to find your way out of on your own. You have to climb that mountain. But what Fu’s painting also affirms is the drive to life, the pulsing of space that like the pulsing of the rain becomes an affirmation of how we are always interconnected, and alive in each other.

Thinking of Aidan’s lovely smile. May peace be with you.

傅抱石《潇潇暮雨》

乙酉五月

抽,纸本,设色

103.5 x 59.5 厘米

南京博物院藏

Fu Baoshi, Soft Rain at Dusk

June 1945

Handscroll, colour on paper; 103.5 x 59.5 cm.

Nanjing Museum. Donated by Luo Shihui, Fu Baoshi’s wife.

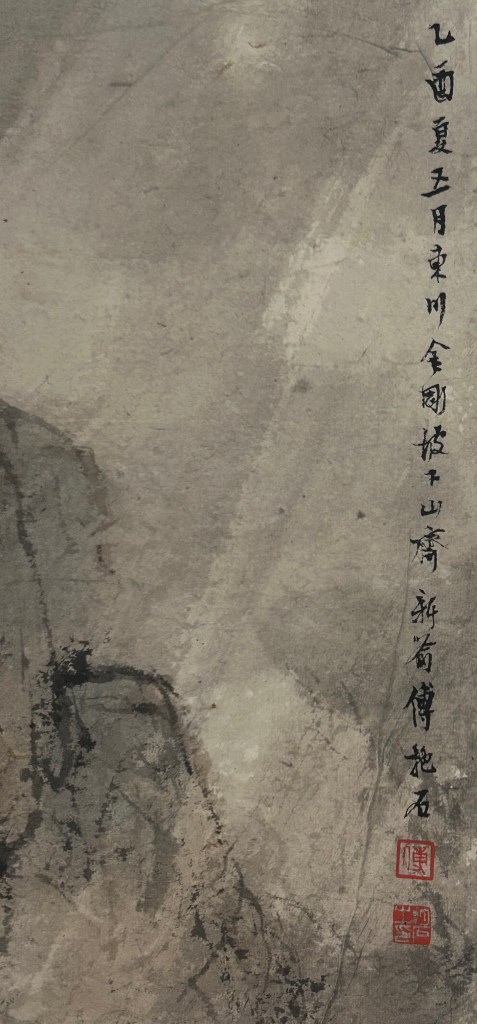

Inscription: 乙酉夏五月,东川金刚坡下山斋,新喻傅抱石

Fu Baoshi of Xinyu in the fifth month of the yiyou summer (June 1945), at his mountain studio at the foot of the Diamond Cliffs in eastern Sichuan.

Beautiful Lisa!!!❤️ Thanks 🙏 Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike

Very moving. Thank you Lisa!

LikeLike