Angkor Complex: Cultural Heritage and Post-Genocide Memory in Cambodia

Exhibition Review Part One

The daguerreotype is free of tarnish and fingerprints. The entrance to Cambodia’s Khmer temple Angkor Thom floats dimly on its surface, grey-blue on silver. The sculptures’ familiarity makes it easier to see the image. It is a familiarity shaped by French colonial-era postcards, or by black and white news reports during the dark years of the Pol Pot regime (1975–1979). But the plate is so clean and new that it also functions as a mirror. The colourful entrance to the exhibition is reflected in it, shadowed by the photographed grayscale temple entrance. Perhaps more aptly, the daguerreotype image creates a miasma through which the looted temple sculptures from Cambodia and contemporary artworks on display in the gallery can be glimpsed obliquely. Viewed straight on, the daguerreotype reflects the face of the beholder peering close.

Daguerreotypes are a nineteenth-century photographic technology in which a light-sensitive, highly polished, silver-plated copper sheet is exposed to light and produces a single image. The technology itself belongs to another time, a colonial era, but when the artist Binh Danh employs it, it becomes a way of questioning all colonial technologies, including the technologies of war (think of shooting a photographic subject just as you would a gun). These are the technologies that transformed Cambodia into a French colony in the second half of the nineteenth century. They were turned on the people of Cambodia during the four-year genocide headed by Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge in which, as curator Nachiket Chanchani points out, “nearly two million Cambodians––a quarter of the country’s population––died of weapon wounds, coerced migration, malnutrition, illness, forced labor, and torture. In these dark years, Angkor Wat and other places of historical significance were sometimes the site of armed skirmishes and at other times havens for individuals unsettled by the war.”

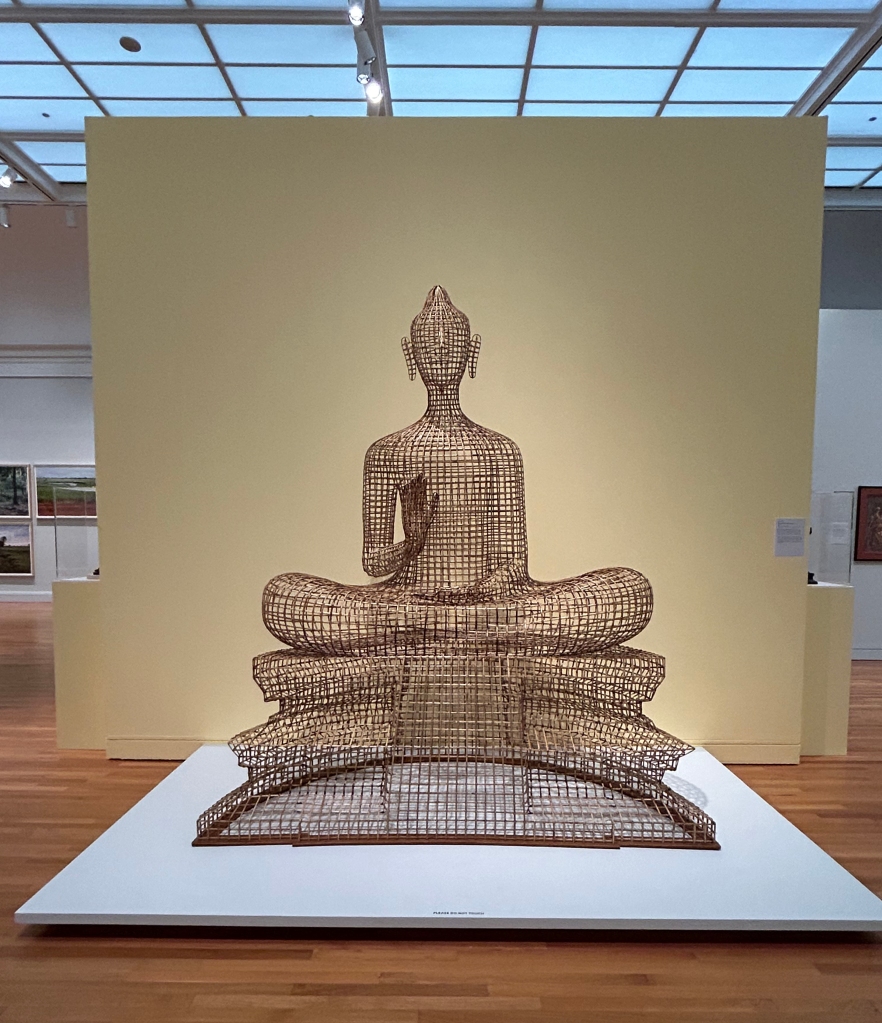

The reflections in Danh’s daguerreotype raise questions about the complicity of the beholder in the horror visited on the Cambodian people. That the daguerreotypes are the first pictures you encounter at the Angkor Complex exhibition thus alerts that this exhibition is not going to permit easy encounter. Though there’s another way into the exhibition, a wrong way, starting at the end and moving backwards through it, marked by a sculpture of a seated Buddha holding his hand up in the “fear not” abaya mudra. It is a peaceful entrance. Yet while the artwork may be welcoming, less confrontational, it too is about the same problem of how technology unmakes the world. The rattan and bamboo structure pays homage to a Khmer technological tradition, which the artist, Sopheap Pich, learned from his father when he helped him as a child to make fish-traps from the same materials. But as the shadow figure behind the Buddha demonstrates, it also is illusory and impermanent, for the good or the bad.

I want to reflect on one final work in the exhibition that reveals fissures in culture and history brought about by acts of violence, and in this case, addressed by technologies of care. Amy Lee Sanford’s Bakong/Break Pot (2013) is composed of a video performance and an installation. The video records the artist at the Bakong temple grounds, where she deliberately drops a terracotta pot, then slowly reassembles it with glue and string. On the museum floor nearby is a perfect circle of restored pots, sherds missing, cracks visible, not entirely whole.

On my walk home from the exhibition, I passed a street light pole that, like any pole in Ann Arbor, my hometown, is plastered with the usual array of photocopied announcements and posters. This pole was covered with a poster that had been taped to it almost a month earlier. It read, “As of: March 18th 2024, 31,726 Palestinians have been murdered by Israel.” Beneath it was an identically formatted announcement, posted when the death toll was 29,092. Checking for the most recent data when I returned home, the number of Palestinians murdered by the Israeli Defense Force had increased to 33,797 (more than 13,800 children and 8,400 women, with an additional 76,465 people injured and more than 8,000 missing). As I write, there are reports that another mass grave has been found. The annihilation continues with the ironclad support of the Biden administration.

Have we learned nothing from the genocide in Cambodia? What does the Angkor Complex exhibition teach us about the unmaking of the world?

Installation views of:

Binh Danh, Buddhas of Bayon from In the Eclipse of Angor Series (2008) Daguerreotype

Binh Danh, Entrance to the Angkor Thom (2017) Daguerreotype

Sopheap Pich, Seated Buddha––Abaya Mudra (2012) Bamboo, rattan, wire, plywood

Amy Lee Sanford, Bakong/Break Pot (2013) Video performance

University of Michigan Museum of Art

Guest Curator: Nachiket Chanchani

On view through July 28, 2024

Part Two will review artworks addressing the ecological disasters in Cambodia that are inseparable from the genocide.

UK Channel 4 News report on mass grave in Khan Younis