To be in crisis is to be out of time.

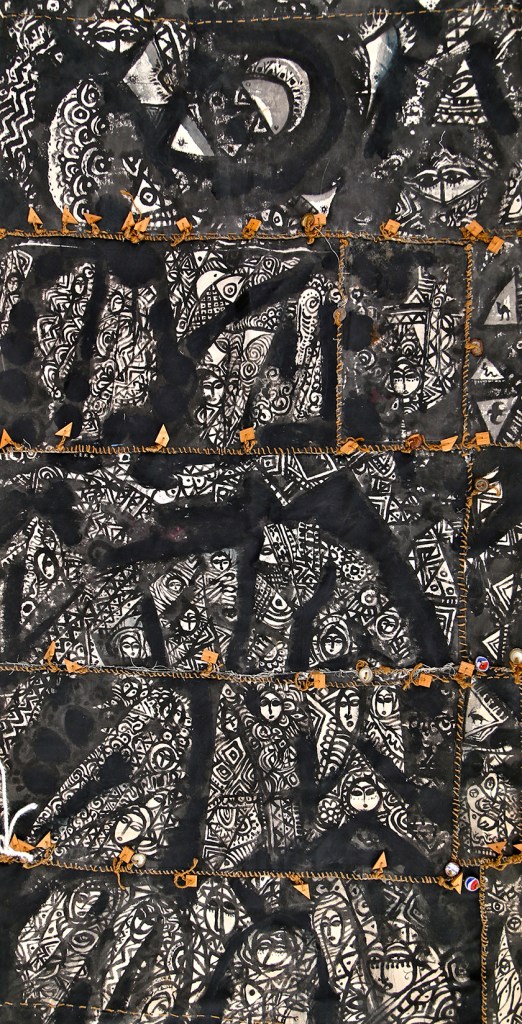

The artwork provoking this thought is long, rectangular, double body-width, composed of small pieces of canvas sutured together with twine (mended, perhaps, though awkwardly), ragged edges fraying. Its surface is densely saturated with images of female faces next to clusters of organic shapes (plants, fish, deer) and geometric forms (nested diamonds, zigzags, triangles). They are rendered in raw strokes of black; some lines sink into the surface; others retain their brushy quality by revealing the texture of the canvas beneath and the energy of the gesture that made them. Throughout there are darker passages, worked and reworked, black on black, pictorial fissures which suggest the shadows of nightmares or dreams. Wooden pieces––protective amulets like one the artist’s mother gifted to him as a child––dangle from the twine, interspersed with bottle caps catching at the light. Splatters of dull red and rusty yellow are barely visible. They are only accidental stains, though. The artist’s medium is black shoe polish.

Aboud Salman. Shoe Polish. 2012. Shoe polish on canvas, twine, wood, bottle caps. Courtesy of the artist.

This is an artwork that radiates the urgency of the moment (think of those stray threads and chunky amulets, the black-soaked fabric, the visceral unpolished immediacy of it all). It is a moment disconnected from narrative; it is a moment out of time. When he painted it, the artist was in crisis, on his own. Aboud Salman was living in a Lebanese refugee camp, separated from his family and his studio in Al Mayadin, Syria, then under ISIS control. His tent-mate tried to steal the painting.

It is the first artwork we encounter in the exhibition The Euphrates Storyteller. The exhibition, however, is about Salman’s return to time. It presents the artist’s story, a chronology of his life in a cycle of twelve paintings. Still, chronology here can only be understood loosely. Time in these artworks is about the slow beat and quick rush of life as it pushes against the logic of “this came first then was followed by that.” Time instead is like the ebb and flow of the Euphrates River (which appears and reappears in the cycle of paintings). It is unstructured, moving to a discontinuous rhythm, transforming.

To be sure, Salman does not have an easy-going relationship with the past. Partly this can be put down to the difficulty of restoration of a time of pain and loss––Salman describes it as “connected emotions and feelings”––in pictures, by which I mean the act of putting something resisting rationality into an orderly story with a beginning, middle, and end. Partly this can be put down to a stroke he suffered and its impact on his memory. A friend relates that afterwards he would play a particular song on repeat for hours while immersing himself in his work, much in the way children engage in repetitive action as they process and remember and learn.

For these reasons, it is fair to ask: how does the cycle of pictures represent the story of Aboud Salman?

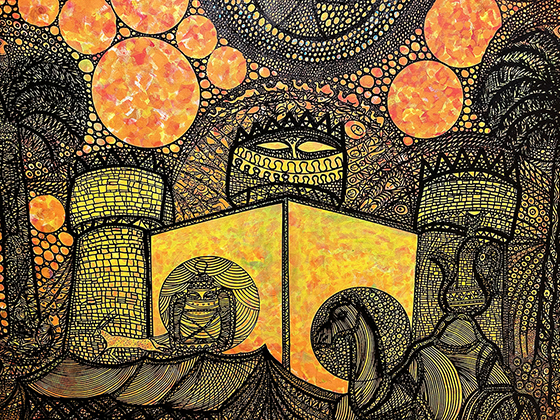

We begin with a painting featuring the city of Deir ez-Zor’s cable-stayed suspension bridge (Al-Jisr al-Mu’allaq) crossing the Euphrates River. More precisely, it is the former bridge, as it was destroyed in May 2013 when the Assad regime targeted it with heavy artillery shells. Salman rebuilds it. In Salman’s picture the suspension towers transform into a memorial. It honors memories of the last years of his childhood, when his mother sold eggs to pay for the bus fare to cross the river so that Salman could buy art supplies in town. The bridge tower is central in the composition, composed of the only straight lines in the picture, painted with thick yellow-green acrylic, and framing small portrait busts of his mother and himself.

Aboud Salman. Deir ez-Zor. Undated. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

Yet to call it a memorial perhaps is to miss the point: the bridge is anthropomorphized. A sun daubed in juicy reds, oranges, and lemon yellows gives the appearance of a head. Bird-fish (flying fish?) stream through the sky around it as if locks of hair. His mother’s magenta-and-violet scarf swirls around the tower like a pair of wings, while birds in profile cascade to either side as if patterns on a bell-shaped dress. Below, at the foot, a boat rests on bubbling cool blues and foam greens of the Euphrates. In addition to supporting the human–bridge, the boat carries candles (seven for each one of his family members), a yoked ox, and fish. The bridge, in sum, transgresses the grave formality of a memorial monument marking a time and place. If it is about the artist as a twelve-year old and his mother, it shows that relationship to be colourful, joyous, about to lift away on wings. And alive.

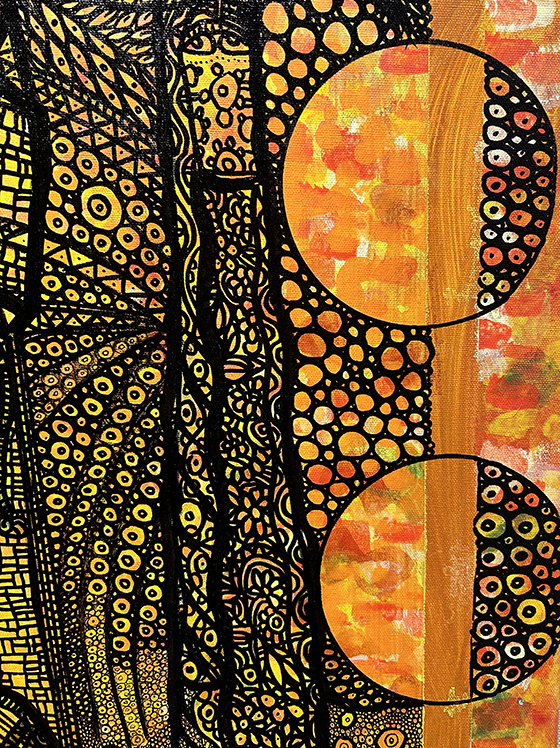

We turn to a painting depicting Salman’s life in his thirties, when he was a fine arts professor in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and dreaming of opening an art gallery in Damascus. At the centre is the famously solid clay and mudbrick gate of Al Masmak Fortress. An image of a child holding an open book (the logo of the school where he taught) floats among multiple suns in the sky with a winged horse (the Burāq, mount of the prophet Muhammad.) Below is the desert: palm trees on either side of the fortress, a Bedouin on horseback, a camel carrying an out-scale samovar, tents, a hawk. The warmth of the deep oranges and deep yellows carries the heat of the Arabian Desert.

Aboud Salman. Riyadh. Undated. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

The figures represented in the painting might recall tourist postcards cut-and-pasted together (and in a sense Salman was a tourist to Riyadh)––if it were not for the eyes. Eyes peer out from a tower in the gate, the book that the child holds, the trunks of the palm trees, the granular design of the background. They interrupt the ordinary, the easy categorization of things and symbols, the temporal beat of the everyday. They trouble those structures of meaning by looking back.

We return full circle to crisis. “This is a sad painting,” Salman says, “and it saddens me more to explain it to people.” The first impression is a mosaic of soft colour: tangerines, corals, magentas, ochres, rose pinks. The outlined shapes are cellular, coalescing around the borders of a map of Syria that is mostly empty but frames a horned skeleton. Salman calls it the “scarecrow of war.” It wears a tattered dress and stands with arms outstretched in a heap of glaring skulls, hanged figures swinging from one arm, missiles headed towards the land masses in its open chest. Its eyes are dilated, above a gaping smile and below a light contour line delineating ears and the top of the head that is just barely visible above the skull, as if the skeletal figure belongs to the world of universal symbolism denoting death and to Syria’s human reality of suffering.

Aboud Salman. War. Undated. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

Contained within the larger painted picture frame are bandaged bodies, a dead child lying on his stomach, barbed wire, townscapes. These are compositional figures and elements that for Salman are “like a crumbling brick wall.” Possibly the metaphor of the wall is in a literal way referring to the colour of rose-tinged limestones in Syria (think of the palette of this painting) or maybe to the Palmyrene funereal tower tombs dating to Queen Zenobia’s time and earlier (the first and second century CE, blown up by ISIS in 2015). In a less literal way, the wall is composed of human remains, the victims of violent suppression by police, paramilitary, and military forces of the ad hoc democracy movement in 2011 and later, the civil war.

Salman’s effort at framing the crumbling wall matters. It is as if he is struggling in his art practice––his storytelling––to contain and make sense of an inexorable, slow fall of bricks making up Syria today by locating it within the boundaries of a scientific map and a straightforward picture frame. That is, it is as if he is trying to put into one deliberately measured time and place a war that by its horrific nature stretches the scansion of chronology out of a familiar rhythm and direction. But in making that effort, he draws attention to its impossibility. In the war-torn landscape, the waters of the Euphrates surge and recede.

There is only one date in the labels and expository prose in the exhibition. On November 23, 2017, Aboud Salman and his family arrived as refugees in Edmonton.

The Euphrates Storyteller currently is on view at the McMullen Art Gallery, University of Alberta Hospital. Monday-Friday 10-5, Saturday 11-5, and Sunday 11-2.

Thank you Lisa:

Such excellent writing and meaningful beautiful work.

Be well, Roy

LikeLike