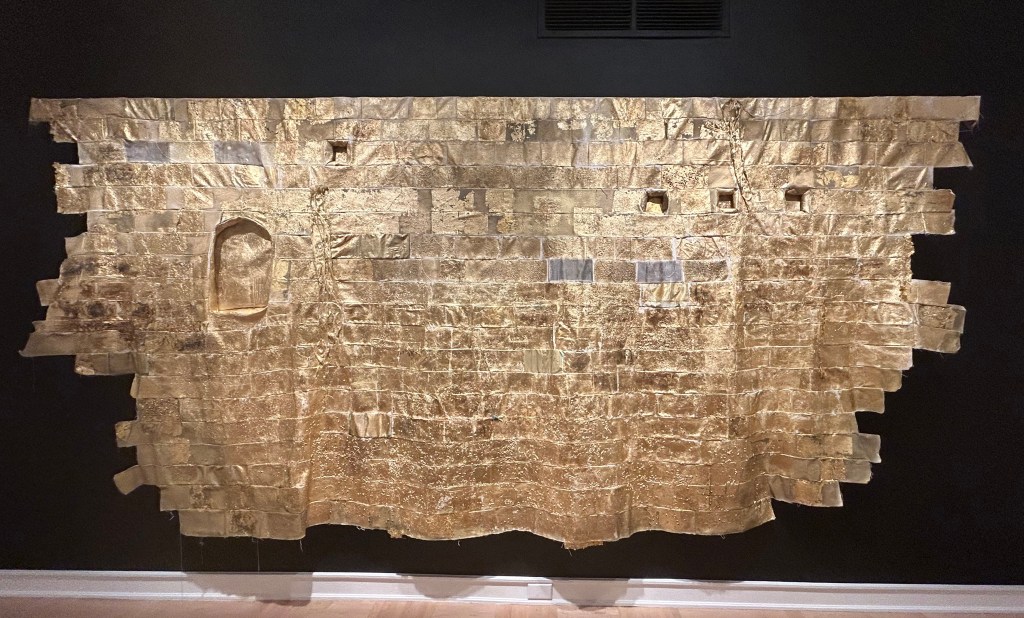

A floating wall is held in stasis. It is dull gold and shimmering, satin soft and hard, like an insect carapace, heavy with paint and lightly frayed. It is a wall that is trying to stop being an exoskeleton of bricks and mortar and start being just rectangles, arches, and squares. Or the other way around. Behind that wall is a space that is as in-between and peculiar as the wall itself. Though to be more accurate, its depth is circumscribed by a museum wall painted black. So: two walls, and between them, space.

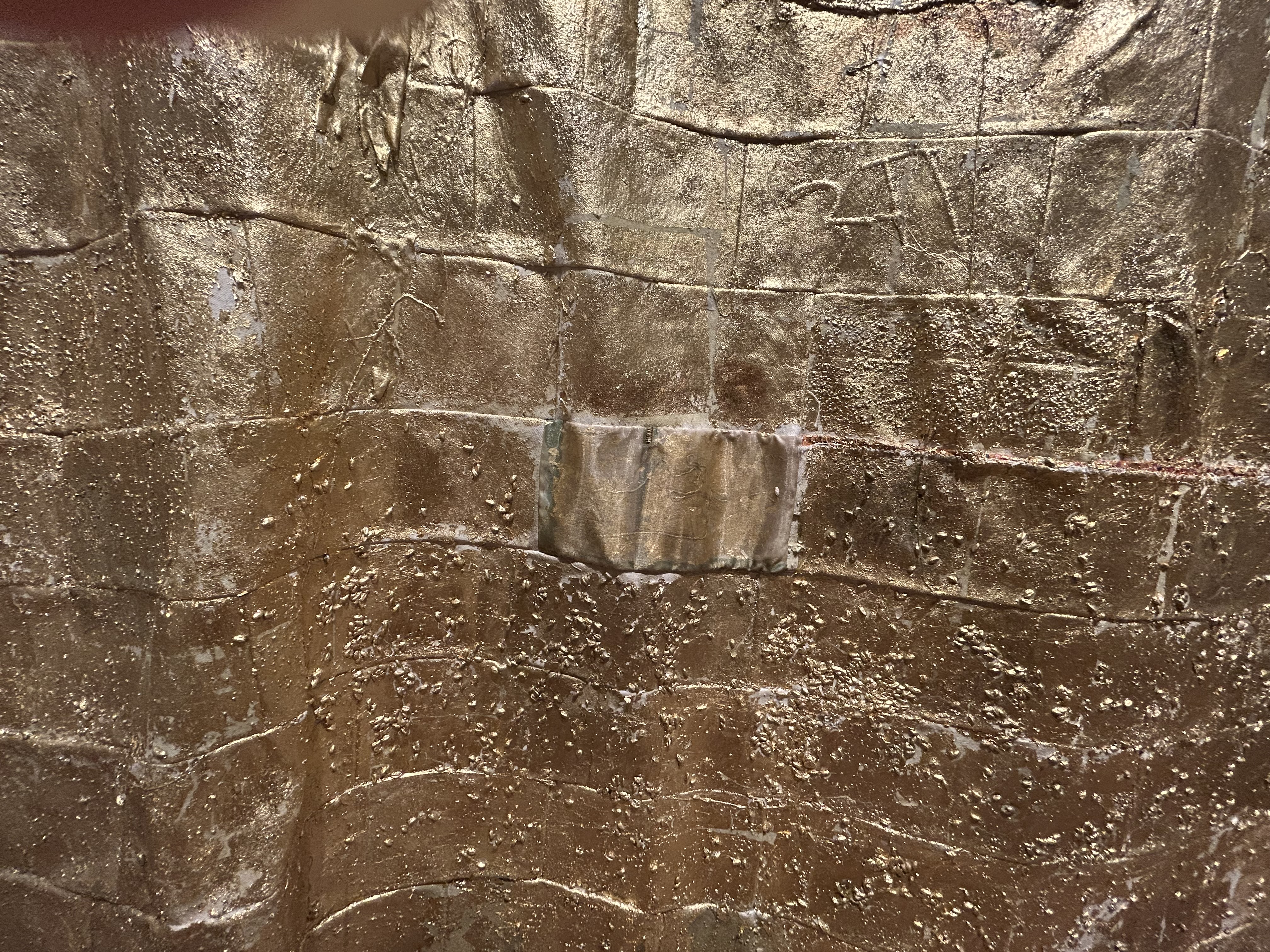

But let’s dwell on the thin gold wall first. The surface is composed of textiles in brick shapes, sewn together. They are not precious, not watered silk or brocade, but mostly are closer to everyday canvas or a heavy gauze. In one corner, between the seams of the bricks, there is a fancy fabric covered with paillettes. The gold paint turns them into texture. In a sense, the wall is an exercise in texture: the paint cascades over it, lifting as if gold leaf in some spots, becoming rough where the artist, Namita Paul, has sprinkled lentils and wheat berries. On some bricks, the paint looks burned, a kind of rusty brown-black. The dimensionality of the wall’s surface is made more literal by a closed jharoka arch and square closed windows at its top.

The installation is said to be based on visceral memories Paul has of being at her grandparents’ newly built home in present-day Pakistan––a home that they abandoned, following the partition of British India in 1947. Her own visit (from her birth town of Jalandar, India?) surely was much later, when the house had already become someone else’s home.

Walls, city, dust. Newly designed domestic architecture in British India tended to be semi-colonial in style, drawing from local red sandstone and histories, like the closely connected houses built wall-to-wall in Lahore that sat on the edge of the roads, with entrances that opened directly onto the streets. In the centre of the multi-storied homes of the wealthy would often be an open courtyard, a shared space and the source of sunlight and fresh air, free from the dusty noise of the streets. All the rooms in the house would face the courtyard. The mardaan-khana (men’s section) was in the front, and the zanaan-khana (women’s section) at the back. Standardized, uniformly sized ghumma brick and stone, popularized by the British, replaced the smaller and thinner Lahori pakkā bricks. There’s much more to the “Anglo-Imperial Vernacular” architectural vocabulary, of course, though not evident here.

History is imprinted onto the bricks. But the gold wall (I suddenly think of it as a shroud) is more than documentary. Curator Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander remarks that the artist is reimagining the façade of her grandparents’ home. To call the labour of making the wall reimagining is more or less right: the artist took a dim black and white photograph as an artefact of the imagination and transformed it into three equally imaginative dimensions. Such reimagining also circles us back to the installation in the gallery. The black wall behind the gold looks as if it could absorb sound and light. It does critical work of adding a mute darkness and depth to the space it creates; it conveys a near invisible institutional presence.

What is the nature of that space? What is the imaginative nature of that space?

The artist reflects,

The rooms we inhabit, the walls we build, the homes we leave behind or remake—we carry them, not just in memory, but in the shape of our longings. My work holds that scaffolding: of space as witness, container, collaborator. In my work, I seek the pull of a doorway, the weight of a threshold, the way light remembers a room.

The gap between one wall and the next is the gap between one reality and the next: dreams embossed in gold versus the highlighted immediacy of things on display in the here and now; a wall that floats loose from its cultural signifiers (yet manages to capture their shadows in gold) versus the black wall’s anonymity; memory of a family’s generations in fraying canvas versus a timeless blank darkness. This is not to decry or celebrate the museum wall. It’s the seeming ordinariness of the black wall that allows us to enter that space in-between, where the weight, light, and pull of Paul’s work becomes tangible and meaningful. It’s not a dangerous space. It’s a space that serves as a grounding and contrast for imagination and reality, both, and a space that allows longing and sensation to interpenetrate.

Namita Paul, Testimony. 2023. Canvas, thread, gold leaf, paint, lentils, wheat, assorted textiles.

Spirit House. Curated by Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, the Robert M. and Ruth L. Halperin Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art and Co-Director of the Asian American Art Initiative (AAAI) at the Stanford University Cantor Art Center, with Kathryn Cua, Curatorial Assistant for the AAAI.

On view at the Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, July 26, 2025–January 11, 2026.

Please visit the artist’s website.

For my musings on the artist Bin Dahn’s powerful chlorophyll prints, also featured in the Spirit House show, please read “From Cambodia to Gaza: Angkor Complex @ the university of michigan museum of art, part two, ecologies of pain“