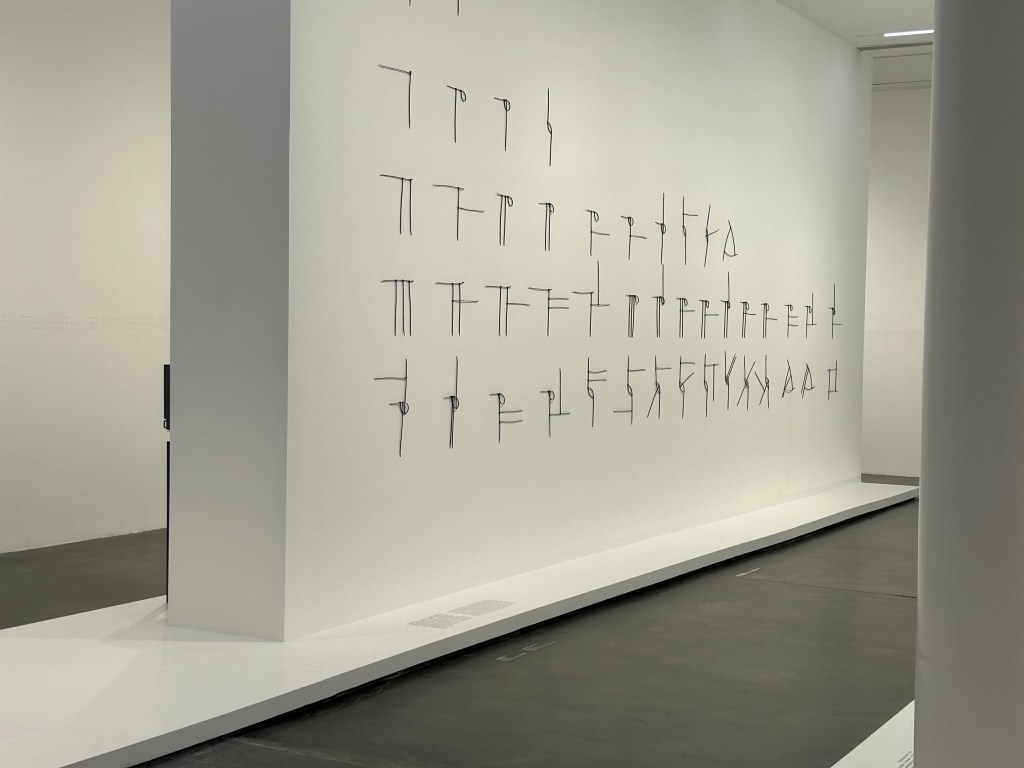

One artwork is penciled on the gallery walls in thin lines, barely perceptible; the other is composed of thick blocks of felt in a mural that extends onto the gallery floor, where it vanishes beneath the feet of visitors. One is silvery, thread-like, near colourless; the other, industrial reds against sky blues, egg-yolk yellows against rusty browns, pale tans against dirty grays. Both artworks are measured, modular, geometric.

There’s a precision to the artworks that extends beyond the visible into the mathematically infinite. Which is to say, the artists, Liao Fei and Chen Ke, are thinking hard about how to see and feel that exact moment when flattened form in two dimensions disappears into three dimensions (maybe four). So even though their projects are opposite aesthetically, they share conceptual space; they reveal that boundary between material form and what lies just within and beyond the power of the eyes to see. They do so to affirm a connective free-floating space out there that relies on geometry and tugs at our inner eyes and imagination.

In Chen Ke’s show, this project is not exactly obvious. Titled Bauhaus Unknown, her artwork is a relatively straightforward examination of the overshadowed women of the Bauhaus (it’s worth pointing out that Chen’s feminist focus is on making visible women who historically have been next to invisible, to return to the question of vision). The first painting you encounter is a portrait of the industrial designer Marianne Brandt (1893–1983), the only woman to graduate from the Bauhaus metal workshop. She is pictured with head tilted to one side. Her facial features, hand, and smock are rendered in heavy strokes of flat oil paint.

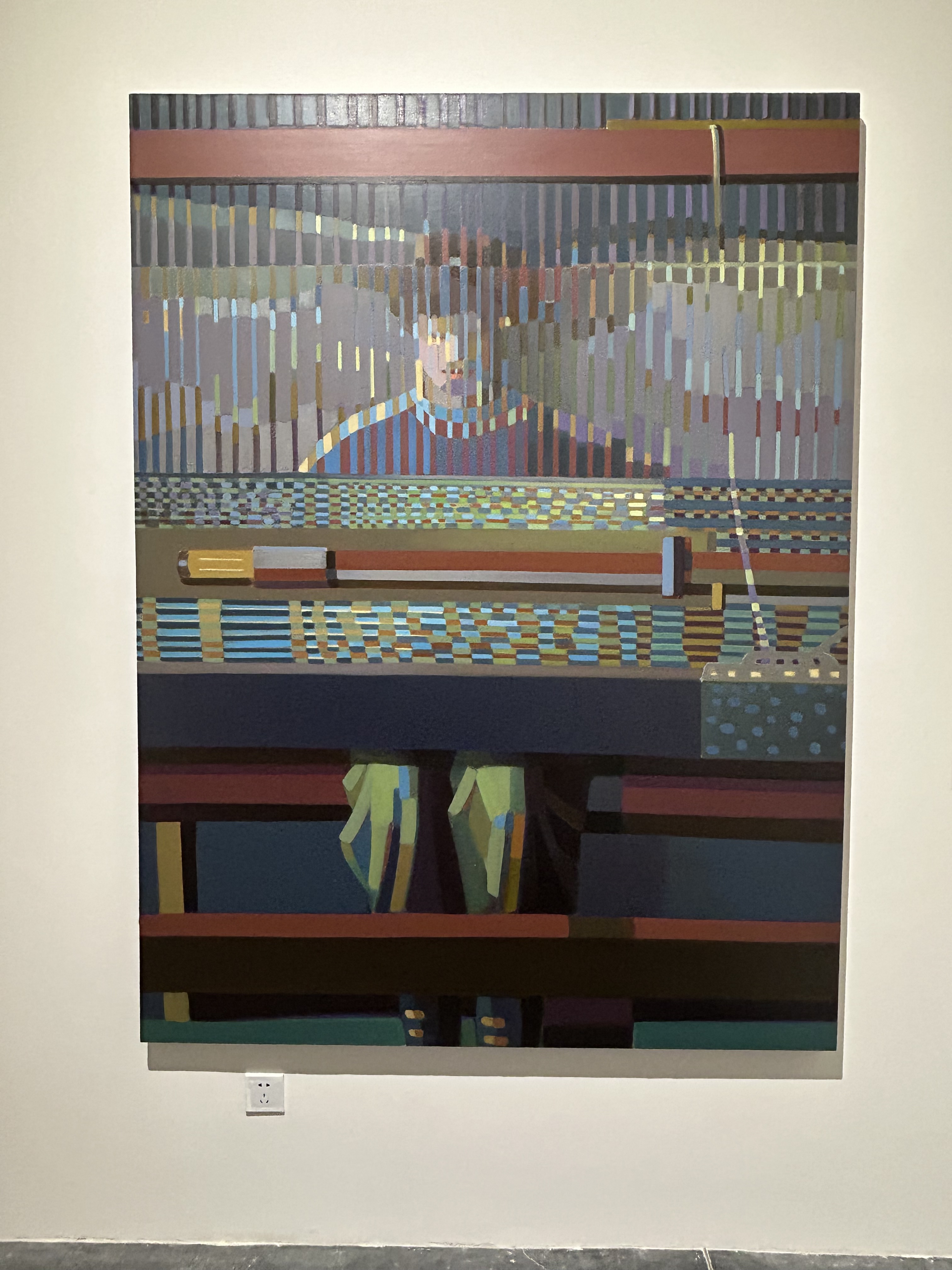

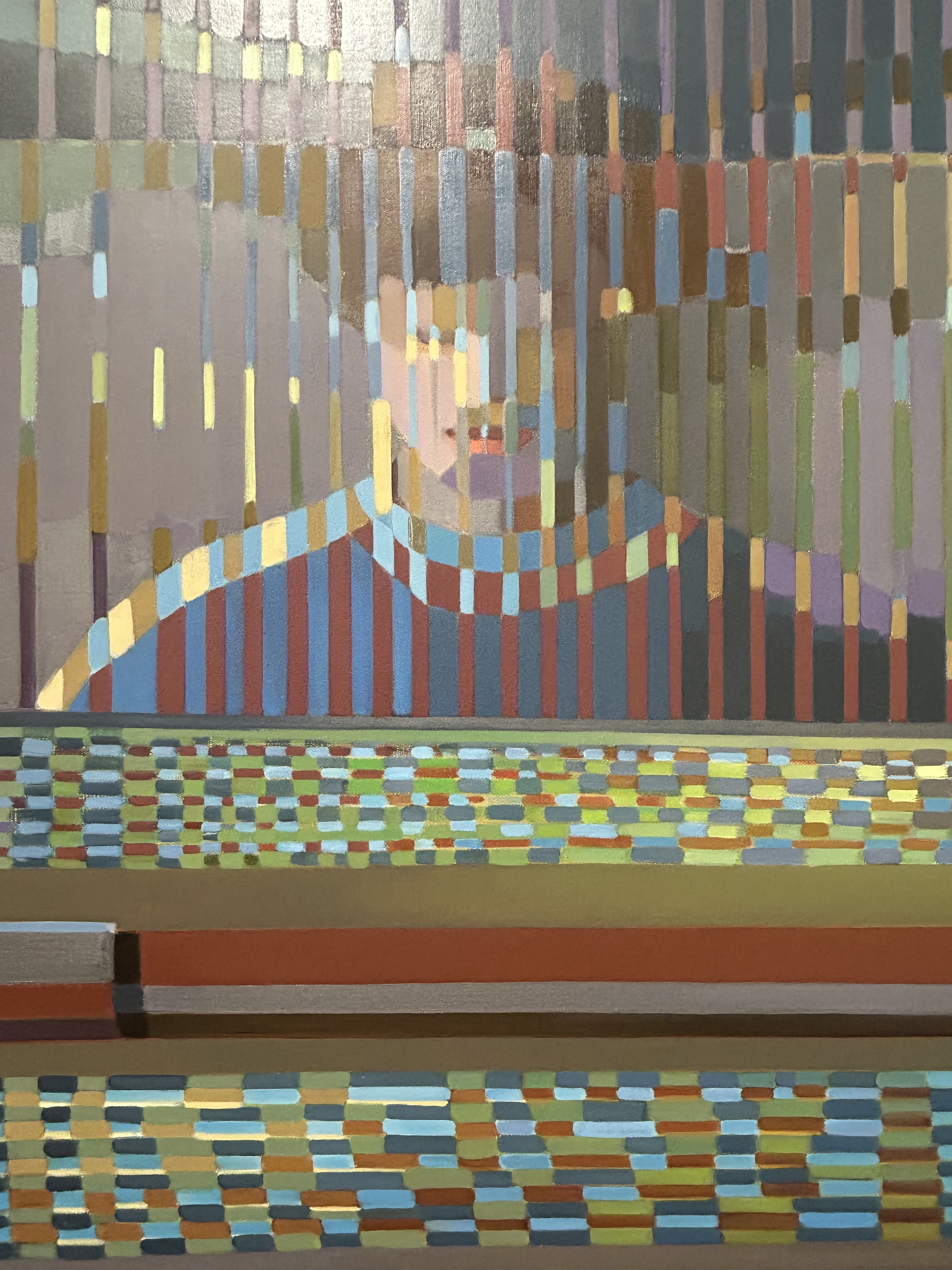

But it also is not the case that Brandt is restored fully to sight. Chen’s hand pulls the figure into abstraction. The colours have a rhythm of their own. Chen’s inspiration is the gridded textile weavings by another of the Bauhaus’ woman professors, the famous Anni Albers (1899–1994). A painting of a woman designer at her loom more clearly demonstrates that supple interplay between figure (representation) and weaving (abstraction). The woman is present; we can see her knees and shoulders. The woman also is not present; the geometry of pea greens and light blues of the textile on the loom before her expands into the rest of the image so that the entire surface becomes textile-like. What is pictured and the picture itself collapse into each other.

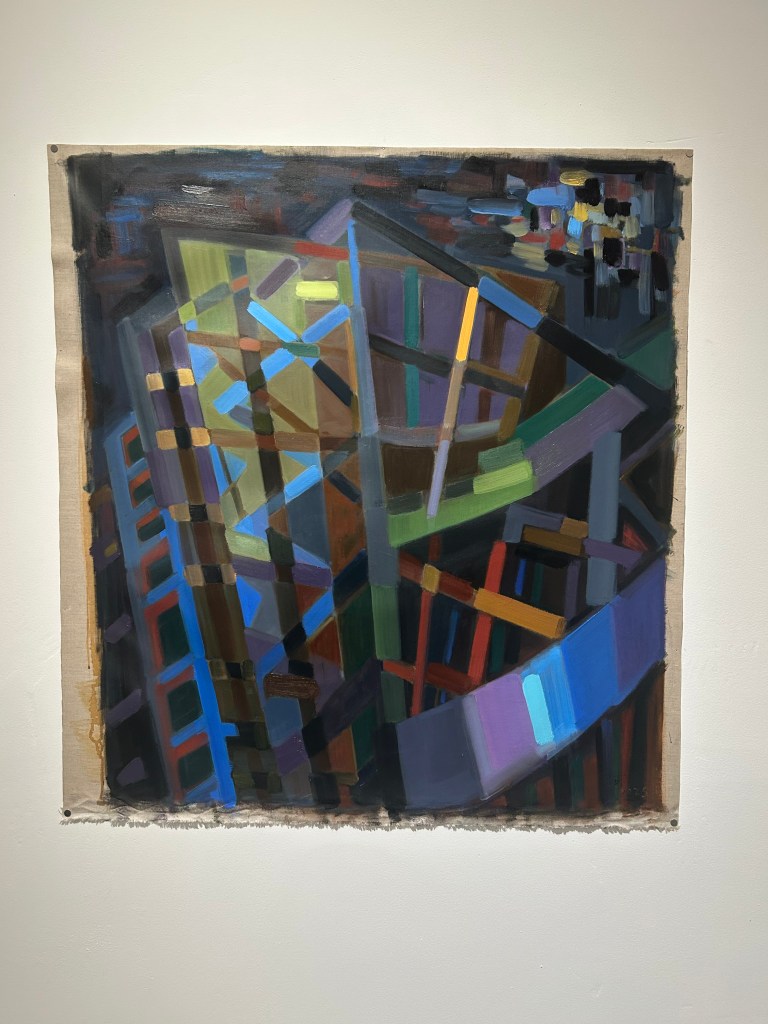

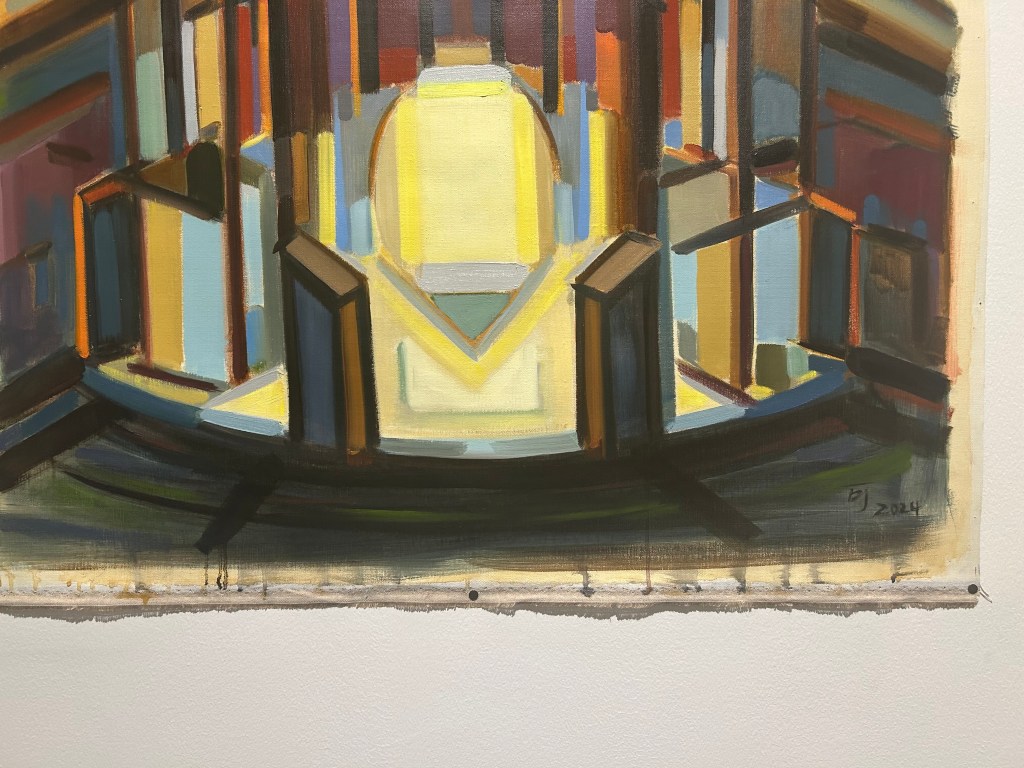

If the portraits connect to weaving (the work of the hand), they also connect to the factory (machine production). The same blunt daubs of oil paint appear in one of the strongest paintings in the show, Factory No. 4. Here the tones are cool blues, purples, grays. But the factory is hot and jazzed up. It swings. The individual bands of colour are gestural and uncontained, the opposite of what you’d associate with factory modularity. You can see how Chen moves her brush across the canvas. Similarly, the edges of the painting are deliberately raw and the canvas edges fray. It’s difficult to say where the picture begins and where it ends.

Factory No. 4 pivots us from the portraits to the actual gallery space, which is a former factory. And it circles us back to the colourful site-specific mural on the gallery wall and floors with which we began this exploration. It is titled Unknown. There’s no Chinese title that would help unpack the English one. The curator points out that the work renders a portrait photograph of famous Bauhaus male designers (so, human figure and abstraction woven together, once again). What is unknown could be the women not pictured in the photograph. But the work also “pays tribute to the colour theory proposed by Josef and Anni Albers which posits that the relationship between colours and space can impact perception.” So equally, the unknown could refer to how we perceive (or fail to perceive) the way that the colours of the artwork enter our own space (not just the wall of colour; we stand on felt, and most of the visitors in the gallery do not seem to notice it against the dull gallery floor). What we do not see nonetheless connects us to greater things, like the space of history.

Seeing All Forms, the title of Liao Fei’s show, more literally translates from the Chinese as “if humans had eyes.” I will review this show in an upcoming post.

Chen Ke: Bauhaus Unknown

陈可:无名包豪斯

Unknown. 2025. Felt.

Marianne and Lilies No. 1 《玛丽安与百合》2025. Oil on canvas.

Behind the Loom No. 1 《织布机后 No. 1》2024. Oil on canvas.

Factory No. 4 《工厂 No. 4》 2025. Oil on canvas.

Liao Fei: Seeing All Forms

廖斐:如人有目

Infinite, Natural Typography 1 《无限自然拓扑》 2017/2025. Charcoal on wall. Dimensions variable.

UCCA Center for Contemporary Art

尤伦斯当代艺术中心

Beijing 798

Both exhibitions on view 2025.5.17–2025.9.7

One thought on “Weaving and Pedaling: Chen Ke 陈可 and Liao Fei 廖斐 at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing (Part 1)”