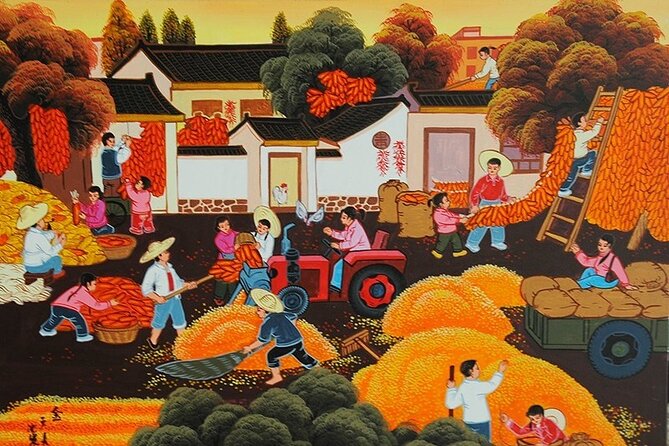

Art for the people (in Chairman Mao’s words) and art by the people emerged at peasant communes during the Great Leap Forward campaign (1958–1961). Called “peasant painting” 农民画, it was what you’d expect of propaganda images. The paintings are easy to read: flat crayola colours, dark contour lines, cartoon-like figures that exaggerate the human form (giving farmers big hands and feet, for instance, to indicate their physical strength). Peasants picture themselves labouring in verdant “peach blossom spring” landscapes and among waves of grain. The message is as clear and as uniform as the textile-like patterns in the paintings: the socialist state is a utopia.

The most famous of these paintings were made in the Shaanxi People’s Commune in Hu County 户县, far to the northwest, where they continue to be produced today. But the practice has managed to survive in other places. Lizifang Village 栗子房镇 in northeastern Liaoning province is about 220 km north of the artist Cui Jinzhe’s hometown of Dalian 大连. It is known for its folk art and paper cuts. It is less famous for its peasant paintings, yet these, too, are made there today.

Cui’s paintings capture the style of peasant paintings, from colour to line, from flatness to clarity. Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that the question her art poses of us is: What does a twenty-first century utopia look like?

Take, for instance, a picture celebrating a birthday gathering. Like the peasant paintings, it is a scene of prosperity and community. Two figures shuck and clean corn cobs. Three make jiaozi dumplings while a fourth pours tea and looks on. Two more roast shaobing flatbread in the wok on top a coal-burning stove. One arranges a dish of greens on a dining table loaded down with a soup tureen, a birthday cake decorated with the peach of immortality, and other dishes. Kitchen utensils and vessels (a rice cooker, teapots, the wok, the cutting board) create rounded patterns across the picture plane; they contrast with the sharp geometric pattern created mainly by the furniture and architecture (tabletops, wall clock, windows, aquarium, and a pet cage). Throughout, animals––a greying Schnauzer, squirrel, goldfish and a turtle, puppy, cat, and rabbits––add visual rhythm to the composition.

Another painting depicts a spring festival 元宵节. A dragon (denoting yang, male) and a phoenix (yin, female) wind through a parade. Giant carp lanterns are held aloft; the Chinese zodiac animals decorate the hats of a group to the right; people dance with umbrellas to the left. The parading figures form a dotted pattern that is replicated by the dots on the lanterns, the flower-dotted landscape, the snow-dotted sky, the dotted heads of distant observers. Like the other picture, the painted colours are flat greens, tomato reds, indigo blues, marigold yellows.

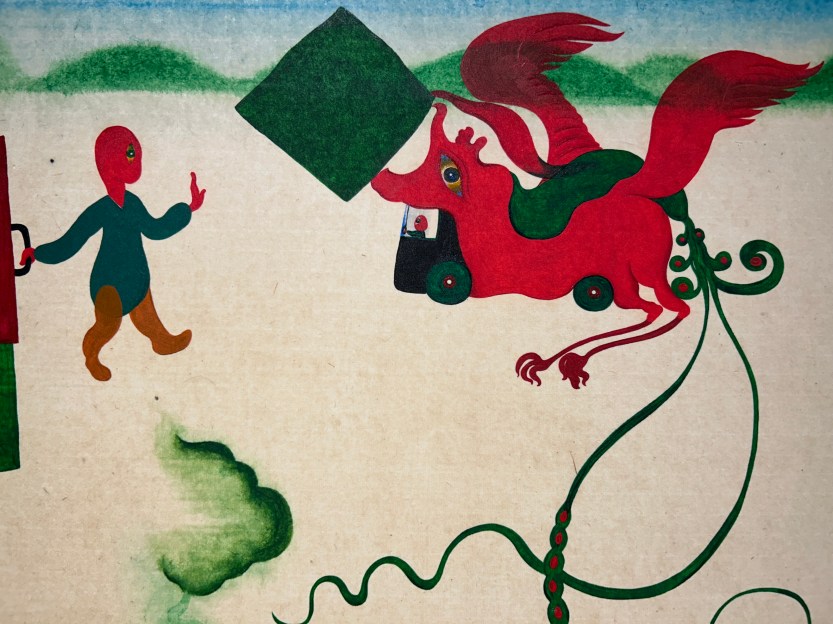

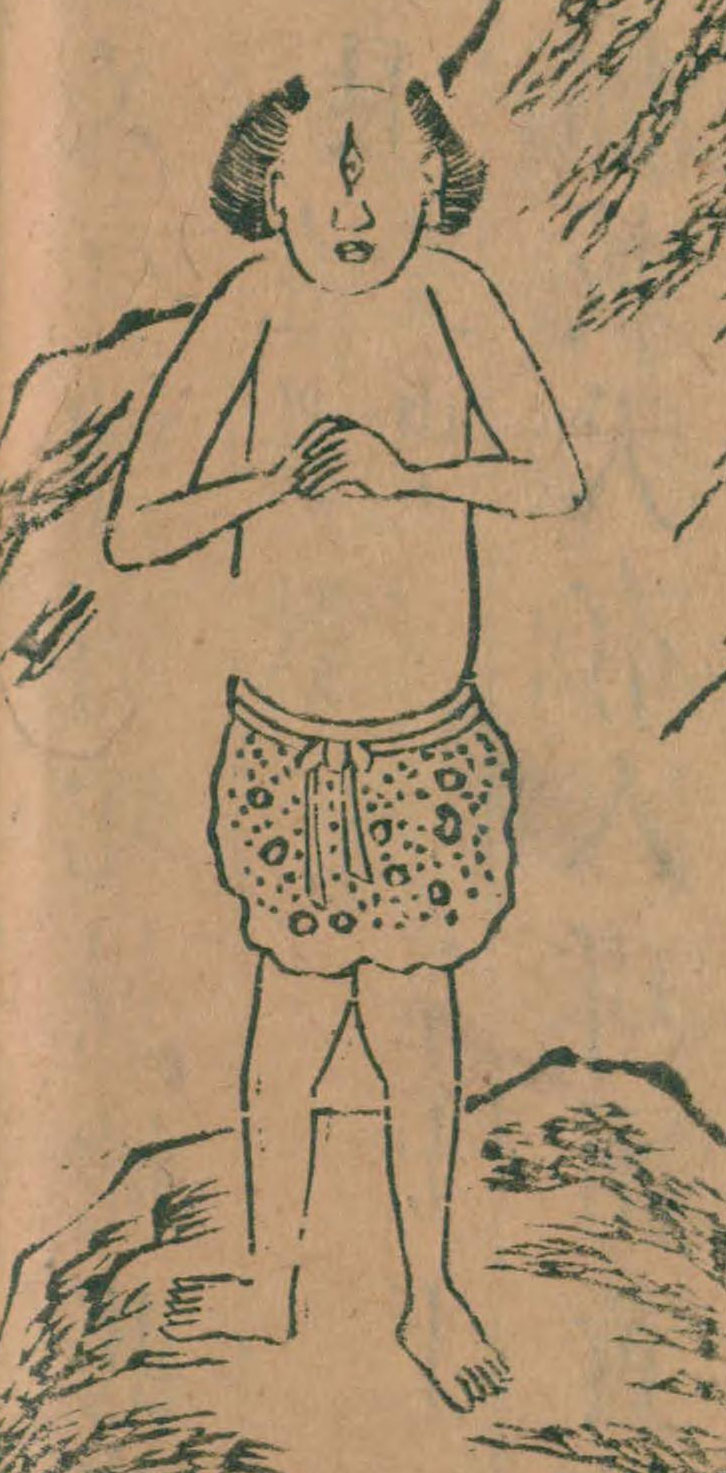

Although stylistically like peasant paintings, and sometimes similar in subject, Cui’s paintings also are dramatically different. The one-eyed red figures reappear in all of them. Some have tails. Their bodies remind me of one-eyed Japanese yōkai 妖怪 monsters and ghosts, the alien Trisolarans in Tencent’s television sci-fi drama The Three-Body Problem 三体, and the transspecies figures from the ancient Chinese Classic of Mountains and Seas 山海经. Mostly they recall the last.

The Classic is an encyclopedic cosmography recording some 550 gods, heroes, demons, foreign peoples, and strange creatures whom an intrepid traveler might encounter on adventures through China and beyond. Among its gods and bestiary, it illustrates the “One-Eyed People” 一目民 (“The people…have one eye in the middle of their faces”) and the “Deep-Eyed People” 深目民 (“The people raise one arm and have one eye”). Similarly fantastical, a phoenix with powerful beating wings and extended legs 凤凰, or perhaps it is a mountain god 神 (“the gods of the [Shaking Mountain] all have the form of a bird’s body with a dragon’s head”), is pictured in green and red in one of Cui’s paintings. What’s different is that in Cui’s imagination, the phoenix-god merges into a truck.

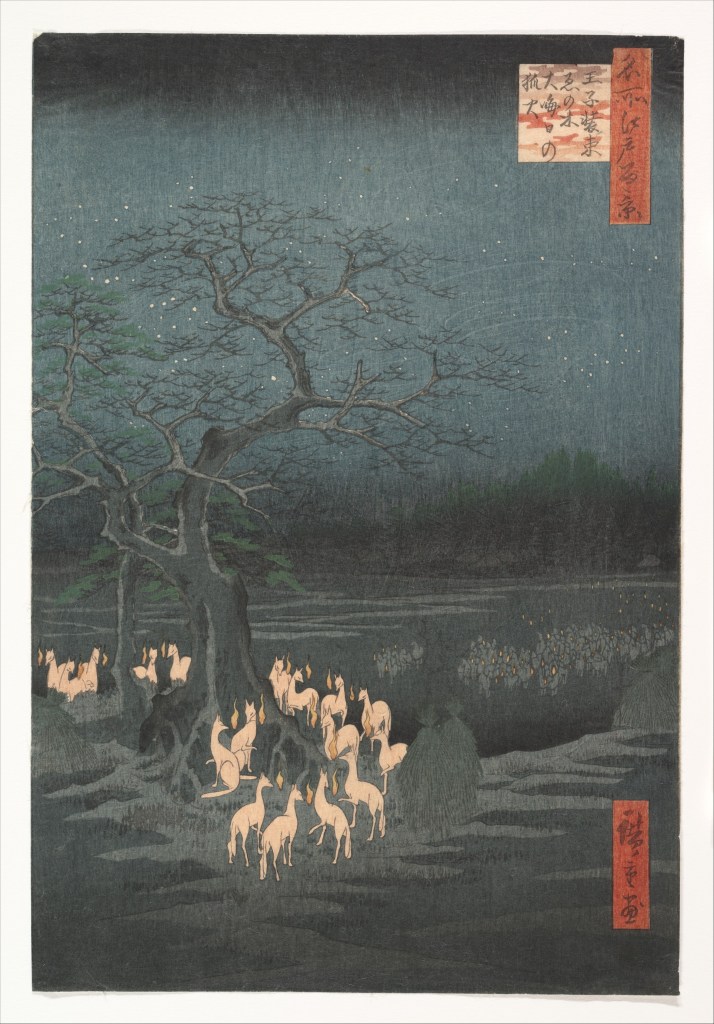

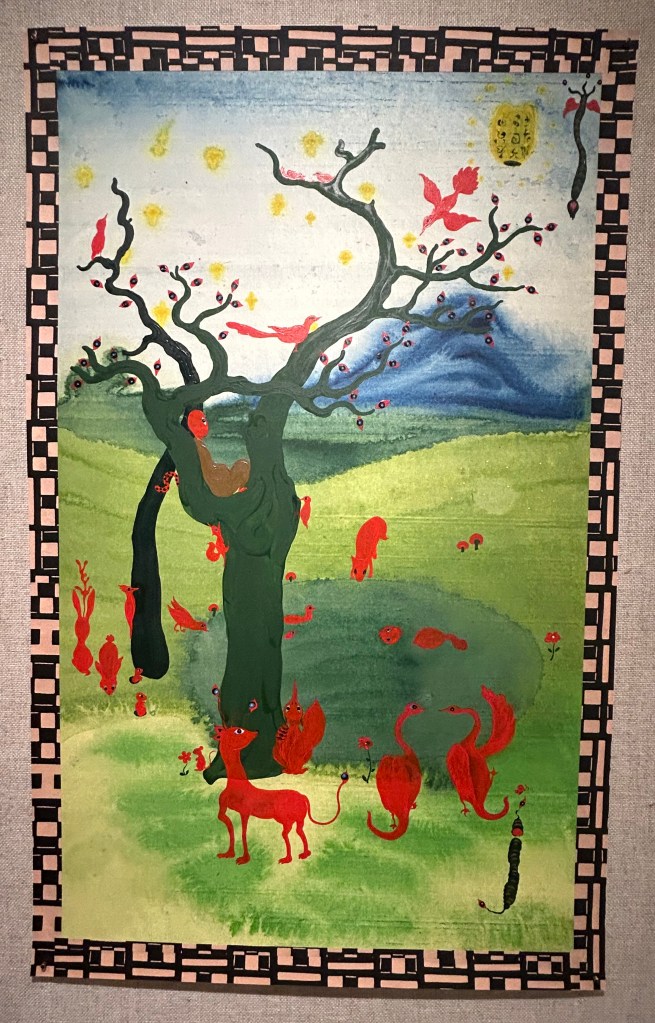

Cui’s environments, too, are made-up, in the sense that they are not identifiable places, and are sometimes cobbled together from disparate visual sources. A number directly recall the colour prints by the Japanese ukiyo-e “floating world picture” artist Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858). One pictorial space features bright red deer, swans, foxes, birds, and other beings encircling a humanoid figure with a striped tail perched in a tree. It is based on Hiroshige’s New Year’s Eve Foxfires at the Changing Tree, Ōji (ca 1857). In Hiroshige’s print, foxes gather at an old enoki tree (just as Cui’s figures do). They are on a ritual journey to Ōji in praise of the god of the rice field, for whom the fox serves as messenger. The landscape itself––the tree––is numinous with supernatural power. Some of that power transfers to Cui’s painting.

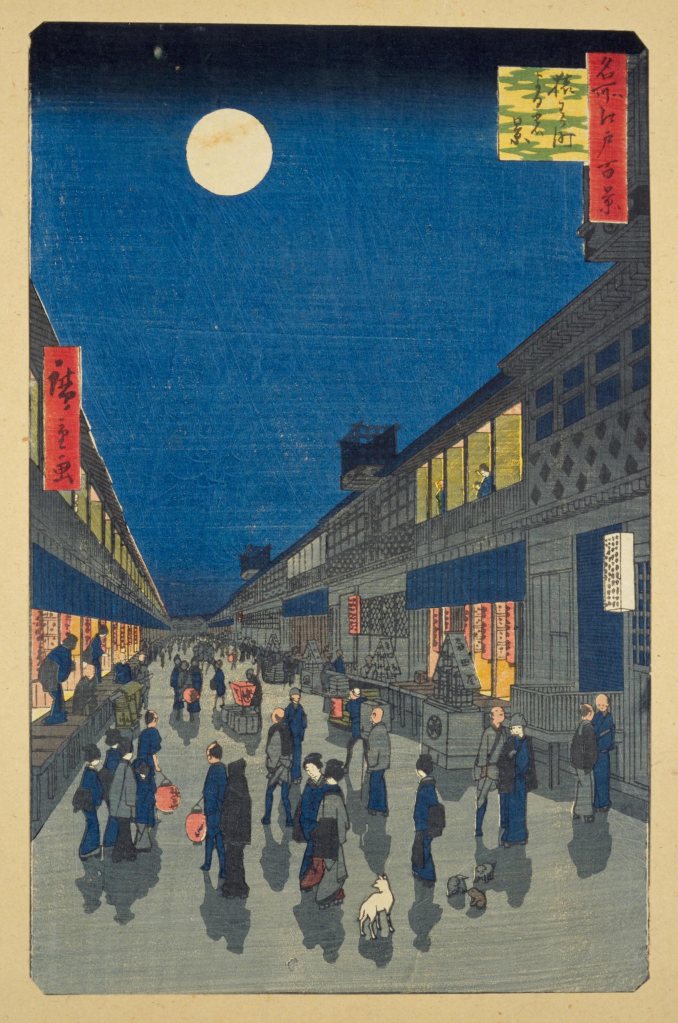

Hiroshige’s Night View of Saruwaka-machi, a kabuki theater district in the city of Edo, becomes a tourist street in Cui’s hands. It is marked by a tram stop called Tian-Di-Ren 天地人, language from the philosopher Mencius (372–289 BCE). The name denotes heavenly timing (meaning the time is right), auspicious terrain, and harmonious people. Tian-Di-Ren is another word for utopia, perhaps. The view is like a daydream. An orange umbrella with one eye is carried upside down. A tree floats gravity free, roots up. Machinery, gigantic flowerpots, people in the street, and monsters sport one eyeball each.

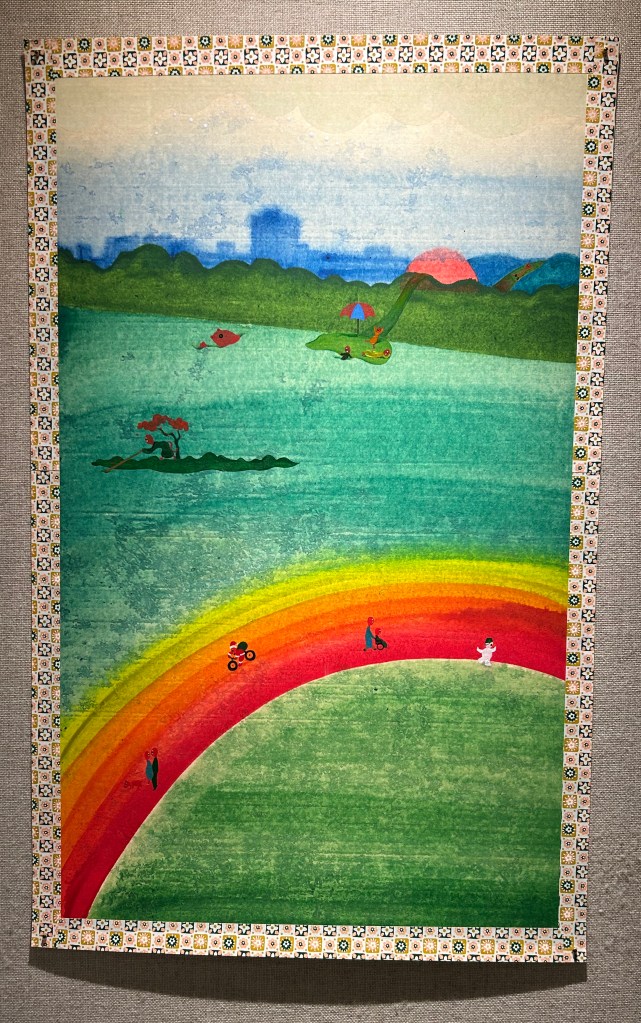

In another painting, the bridge from Hiroshige’s Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake turns into a rainbow. A low-lying skiff becomes a floating spit of land. The grayscale bank in the rainy distance turns into sunny green hills in front of a primrose blue cityscape.

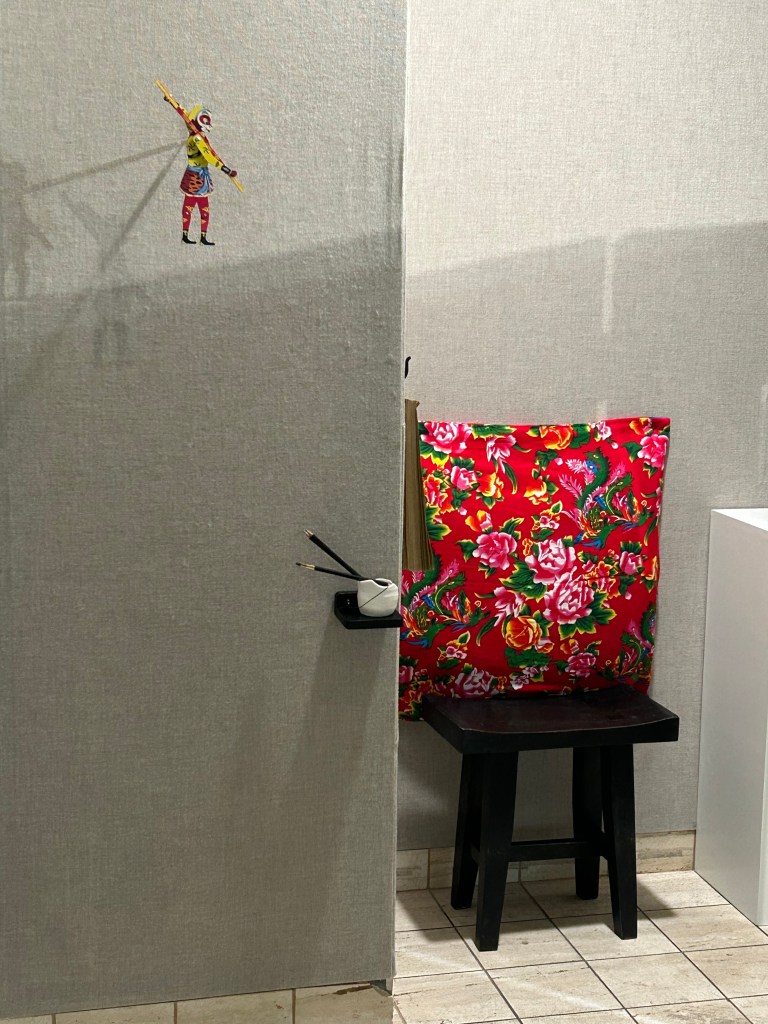

Such quotationalism does critical work. It unhinges the artist’s vision of utopia from Maoist rural socialism. It anchors imagination to global visual culture. It integrates the human and more-than-human worlds. Such beings and spaces we might imagine the Monkey King Sun Wukong (present in the gallery as a puppet) would encounter on his twenty-first-century journey towards the West, represented in the gallery by meditational platforms and stelae evoking the western Buddhist cave temples of Dunhuang. (The Monkey King puppet is displayed next to a cheerful pillow covered in a socialist-era-patterned textile and a chair on which visitors can rest to jot down thoughts as they make their own personal journeys around the show). In the absence of political propaganda, the paintings open “spaces of comfort, reflection, and connection,” in the artist’s words. They have a spiritual orientation. Utopia, in Cui’s view, is inclusive and connective, warm and embracing.

To be sure, there are paintings that are less quotational in nature. For example, one painting depicts the familiar sight of patients queuing for Covid testing. Doctors and nurses in Hazmat suits become even more strange because of their single eyes behind plastic masks, and the red flower petals or drops of blood drifting through the air.

Possibly the strongest work in the show depicts a group watching a city nightscape (Shanghai?) from the deck of a boat. It is washy, blurred in the reflection in the water, practically immaterial. On board, creatures that dwell in the water––a baby turtle, starfish, prickly sea urchins (nestled close to a neck), a mermaid wearing a backpack and toque, air-borne jellyfish––observe the view. They share space with a marvellous elephant-nosed, winged, and three-tailed figure, a seagull-like female in evening dress and stole, a clown, and a child wearing a t-shirt sporting a Buddhist reverse swastika, seated in conversation with a sentient watering can and a friend in a purple hoodie growing a leafy horn on her forehead. There are eyes everywhere––looking back at us, at the city, and at each other.

These final paintings remind us that utopia is not so far away. It does not only exist in daydreams and mystical places. The extraordinary can be glimpsed in the everyday. It can become visible even in the most isolating of moments, such as the pandemic, and illness. The paintings reaffirm for us the magical power of simply being in the world. They reaffirm for us that our everyday experience holds the promise of utopia.

Cui Jinzhe, Home

McMullen Gallery – Site #19

8440-112 Street NW, Edmonton

On view June 2 – July 20, 2025

Monday-Friday: 9am-7pm

Saturday-Sunday: 11am-5pm

Comparative images:

Peasant paintings 农民画, undated. Gouache on paper.

Night Parade of a Hundred Supernatural Creatures (Hyakki yakō 百鬼夜行). Handscroll; ink and pigment on paper. National Library of Japan image database.

Screenshot of Trisolarans from Tencent’s Three-Body Problem 三体 (2023).

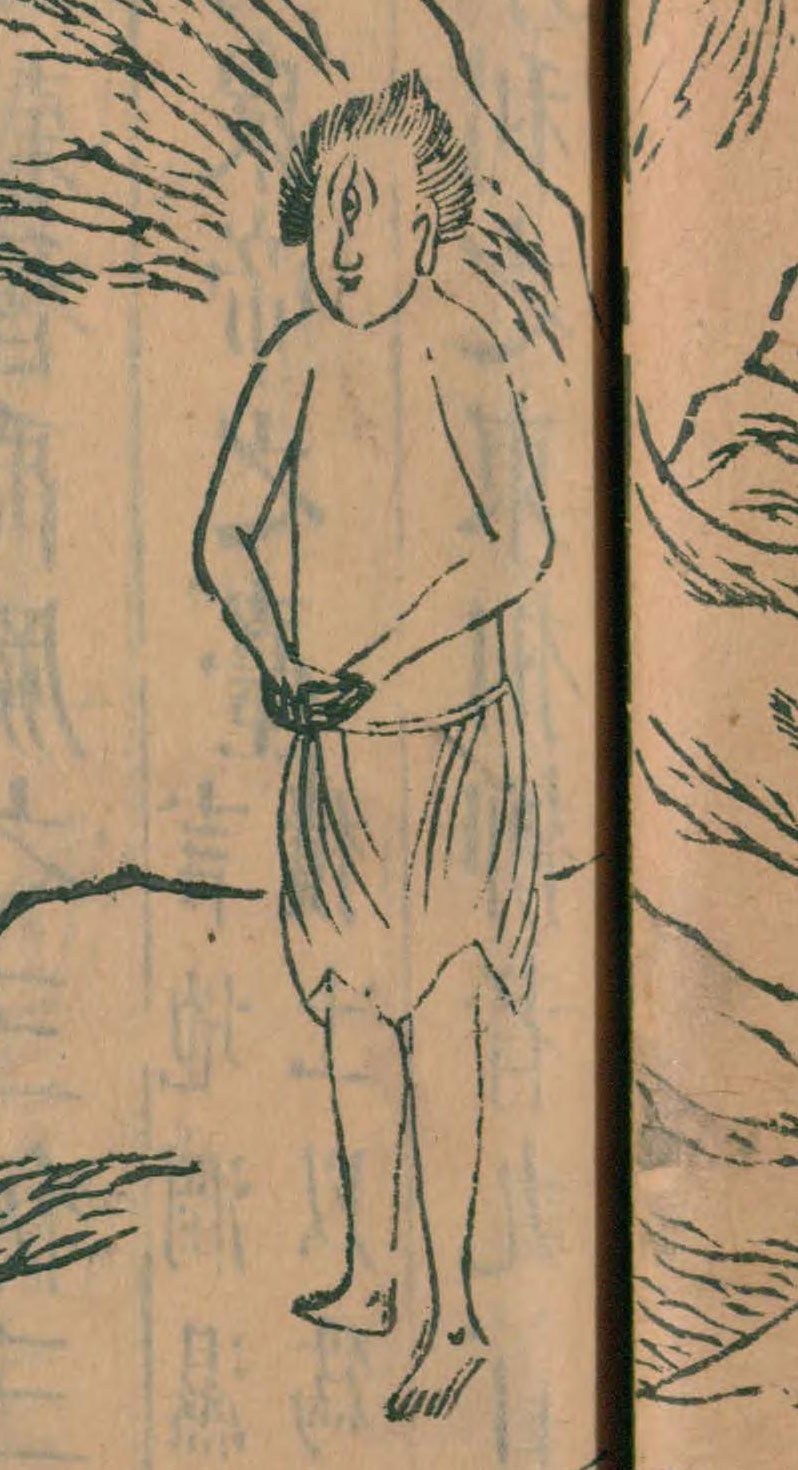

Woodblock print illustrations from various imprints of the Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shanhaijing 山海经).

Utagawa Hiroshige 歌川広重. New Year’s Eve Foxfires at the Changing Tree, Ōji (Ōji Shōzoku enoki ōmisoka no kitsunebi 王子装束ゑの木大晦日の狐火) from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo hyakkei 名所江戸百景). Ca 1857. Polychrome print. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Utagawa Hiroshige 歌川広重. Night View of Saruwaka-machi (Saruwaka-machi yoru no kei 猿わか町よるの景) from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo hyakkei 名所江戸百景). 1856–58. Polychrome print.

Utagawa Hiroshige 歌川広重. Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake (Ōhashi Atake no yūdachi 大橋安宅夕立) from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo hyakkei 名所江戸百景). Ca. 1857. Polychrome print. Metropolitan Museum of Art.