What is courage? How is it visible to us?

The Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation de l’Isère defines courage. It does so by asking in slightly different terms about the meaning of the Résistance––historically, through the lives of the Vercors maquis (short for Maquisards, a Corsican term denoting Résistance fighters), and further, about the valence of courage now, when there is an urgent need to reflect on the enduring value of human rights and act with courage to protect them.

The first thing you see at the museum is the mural on the courtyard walls. There are seven portraits rendered mainly in blacks and pale blues, as if black and white photographs.[1] Contour lines curve nose into eyebrow, lip, chin. They are graphic; they seem carved into the wall permanently, like woodblock prints. Agitated flourishes of the silvery white, red, and azure blue of the Tricolore––fireworks of colour––frame and enliven the portraits.

These are the faces of French men and women who fought during World War II against the undoing of democracy and the violent cleansing of “enemies” at home––the left, gypsies, Jews, gay men, immigrants. They fought against the illogic of the Fascists’ mobilizing passions, summarized by journalist Daniel Trilling as “a sense of overwhelming crisis and victimhood, a fear of the decline of one’s group, a lust for purity and authority, a glorification of violence.” They fought for Republican law. Fighting drew on unwavering faith that oppression of one social group meant the oppression of all. It depended on an unwillingness to retreat during moments of fear. It enacted courage.

Replicated on the mural in stencil serif is a poster dating to July 3, 1944, that reads, in part:

The French Republic

LIBERTY EQUALITY FRATERNITY

PEOPLE OF THE VERCORS:

On July 3, 1944, the French Republic is officially restored in the Vercors. From this day on, the Vichy decrees are abolished, and all Republican laws have been reinstated.

Residents of the Vercors, it is in your midst that the great REPUBLIC has just been reborn. You can be proud of it. We are certain that you will know how to defend it. We would like July 14, 1944, to be an opportunity for the Vercors to further demonstrate its Republican faith and its profound attachment to the great Fatherland.

LONG LIVE THE FRENCH REPUBLIC!

LONG LIVE FRANCE!

LONG LIVE GENERAL DE GAULLE!

For the National Liberation Committee,

President Clément

The mural neatly captures the museum’s strategy: first, to give courage a face; and second, to give courage a voice.

Yet this isn’t as straightforward as it might seem. The museum’s curators and historians acknowledge the complexities of their project. Take the brochure that you’re handed when you enter. The cover is a photograph in grayscale. A young woman dressed in bulky farmers’ clothes with a bouffant hairstyle and glasses stands smiling for the camera. Slicing through her face and body are rectangular windows that reveal the same portrait image on the next page, printed in green tones. Open the cover, and that full portrait becomes visible, and we learn that she is Marianne Cohn, “social worker, aged 18 in 1940,” that her wartime alias was Colin, and that she was “a member of the Zionist Youth movement (MJS) who helped rescue Jewish children. She was murdered by the Gestapo on the night of 7 July 1944.” Opposite is a full-colour image of the museum with the same windows in the brochure cutting through its façade. What you see through those windows are your own hands, holding the brochure.

The brochure does important work. It reveals the difficulties of writing a narrative about the Résistance when much about it cannot be fully seen or heard (though it can be glimpsed, as if through windows), precisely because the Résistance fighters hid themselves in the mountains, and belonged to disparate groups (until 1943, and likely even afterwards, the Résistance was not a monolithic entity). It shows us that nonetheless the museum is a form of mediation and connection between clandestine acts of courage (such as Colin’s rescue of Jewish children) and ourselves (our hands).

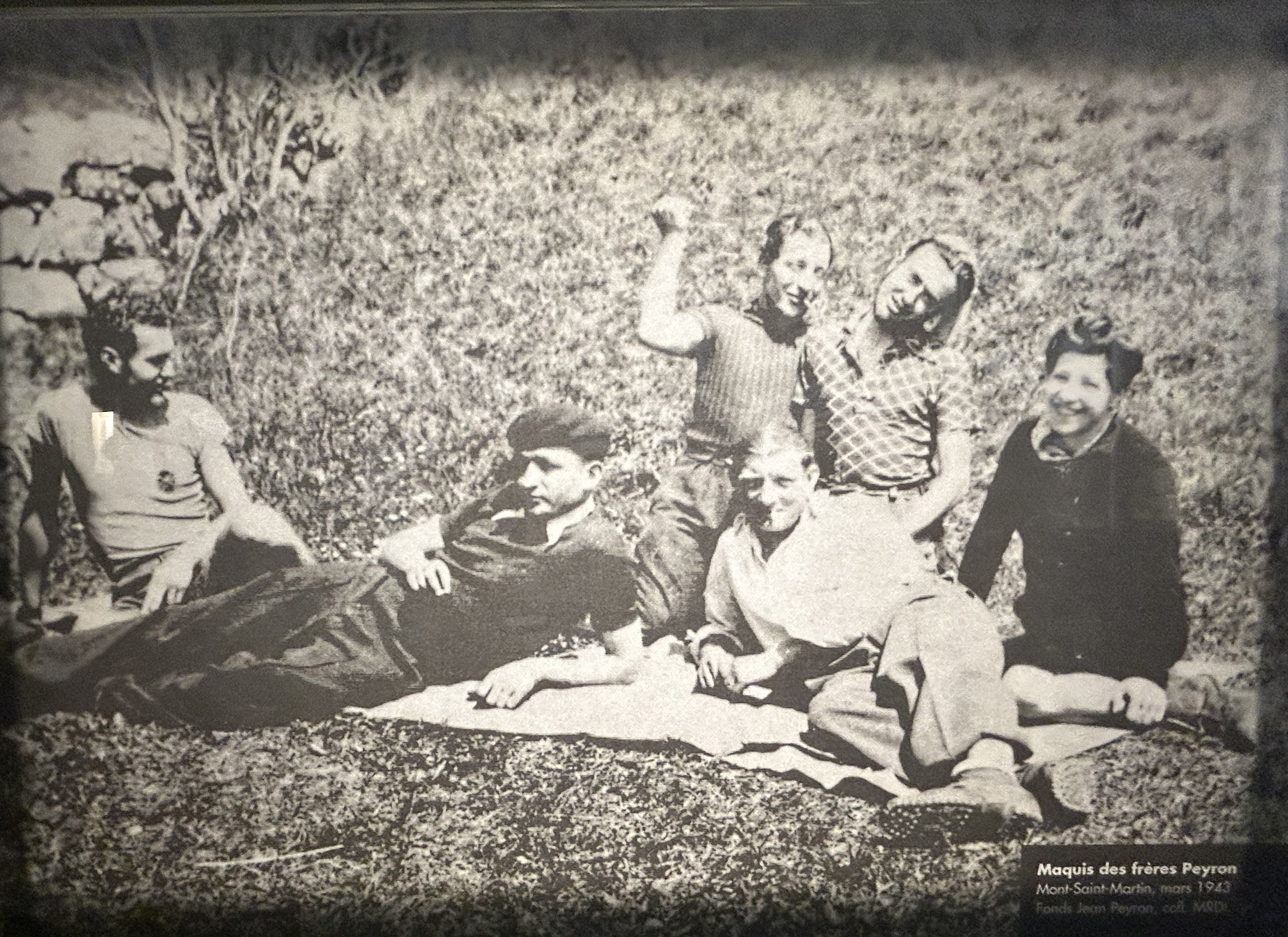

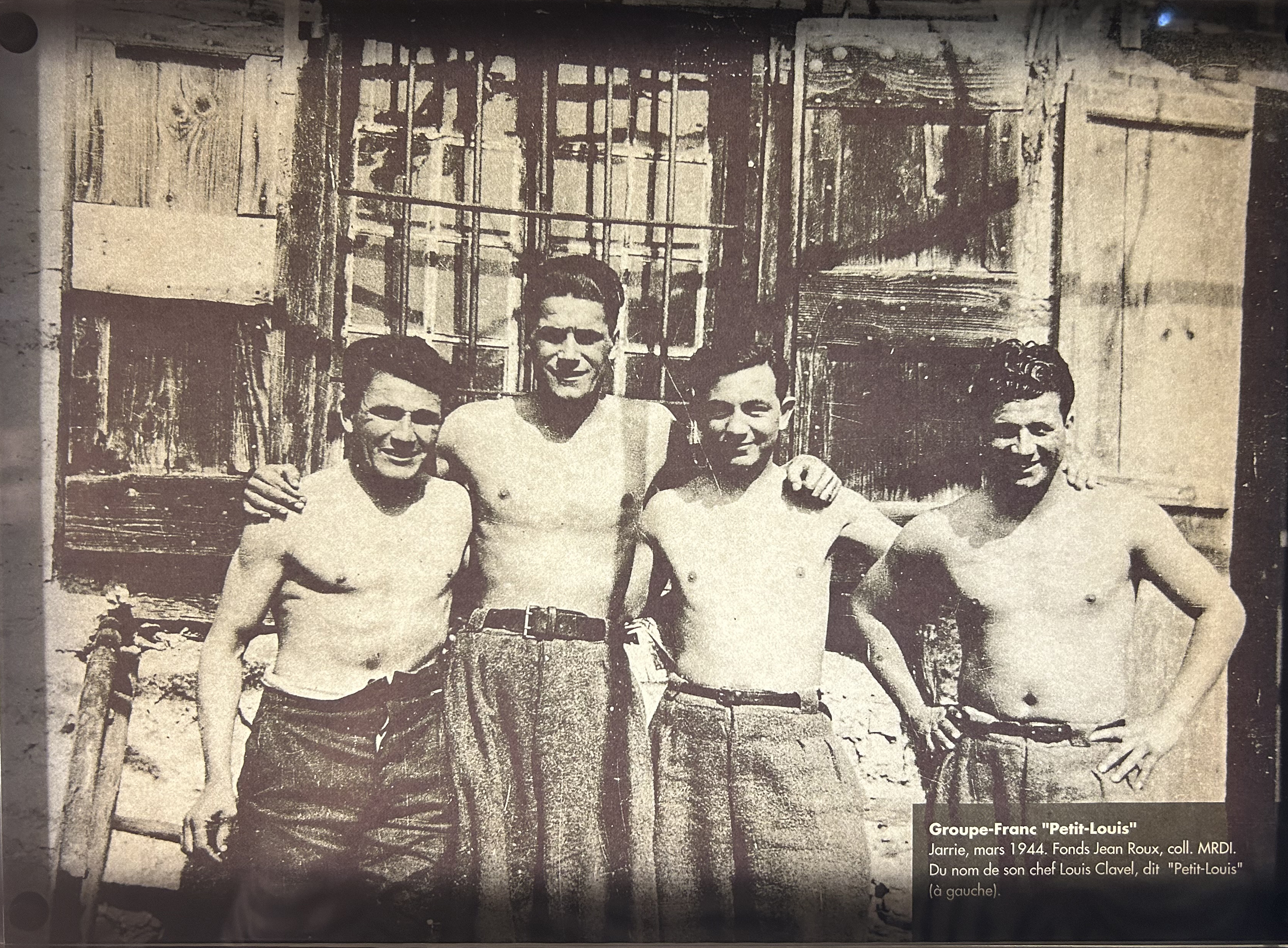

The photograph is the dominant visual form throughout the exhibition spaces. To be sure, there are gas masks, the yellow six-pointed Star of David badge worn by Jews, a three-dimensional map of the French Alps with lights for each of the maquis units and for their attacks on fascist and collaborator armories and strongholds, the stamps used to falsify identification papers, and other tools and things. But mostly what you see are faces: housewives, farmers, café owners, professors, Catholic priests, children, soldiers who deserted the Vichy army for the maquis, freemasons, the Grenoble mayor, those who abandoned official government positions to work for the Résistance.

One installation acknowledges that these photographic traces come to us from deliberately hidden lives. Photographs of maquis centred in Grenoble are installed on empty steel chairs around a stove in a darkened room. It is a replication of the dining room at 4 rue Joseph-Fourie in which Marie Reynoard, teacher at the lycée Stendhal, set up the discussion group that would become the Combat Resistance group. That the chairs are empty speaks of loss: Reynoard was to be arrested and deported by the Nazi collaborator Jean Multon in 1943 and died in the Ravensbrück concentration camp.

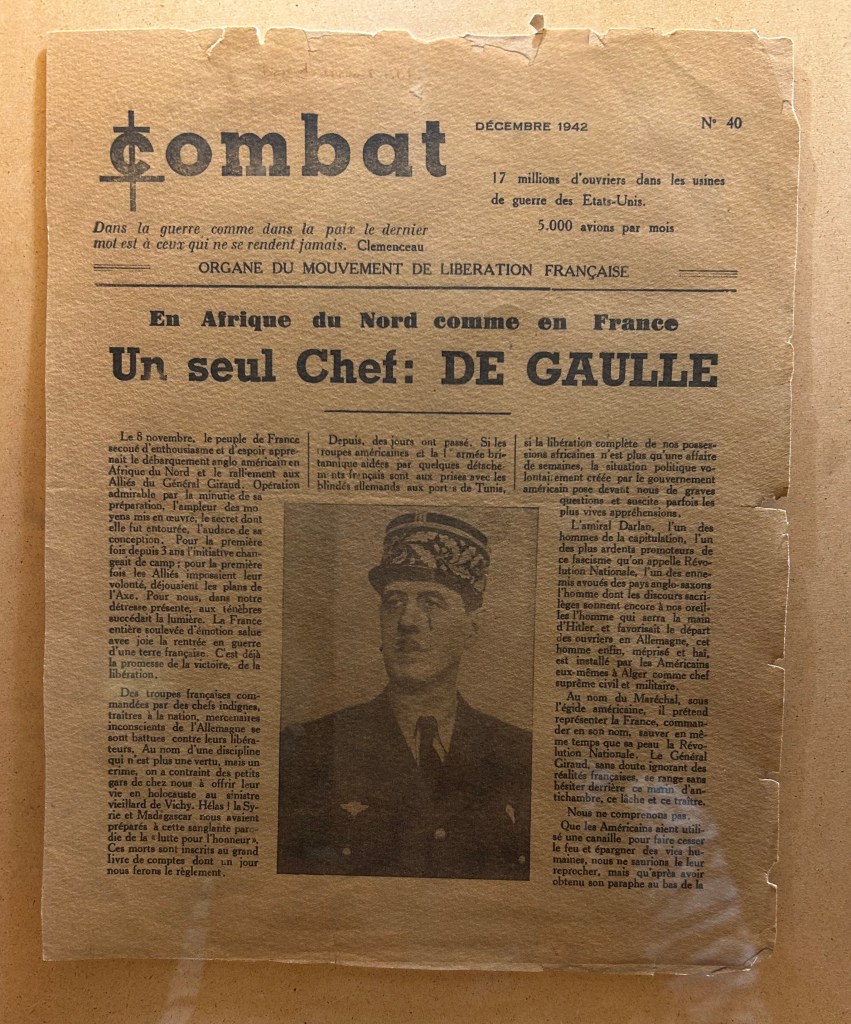

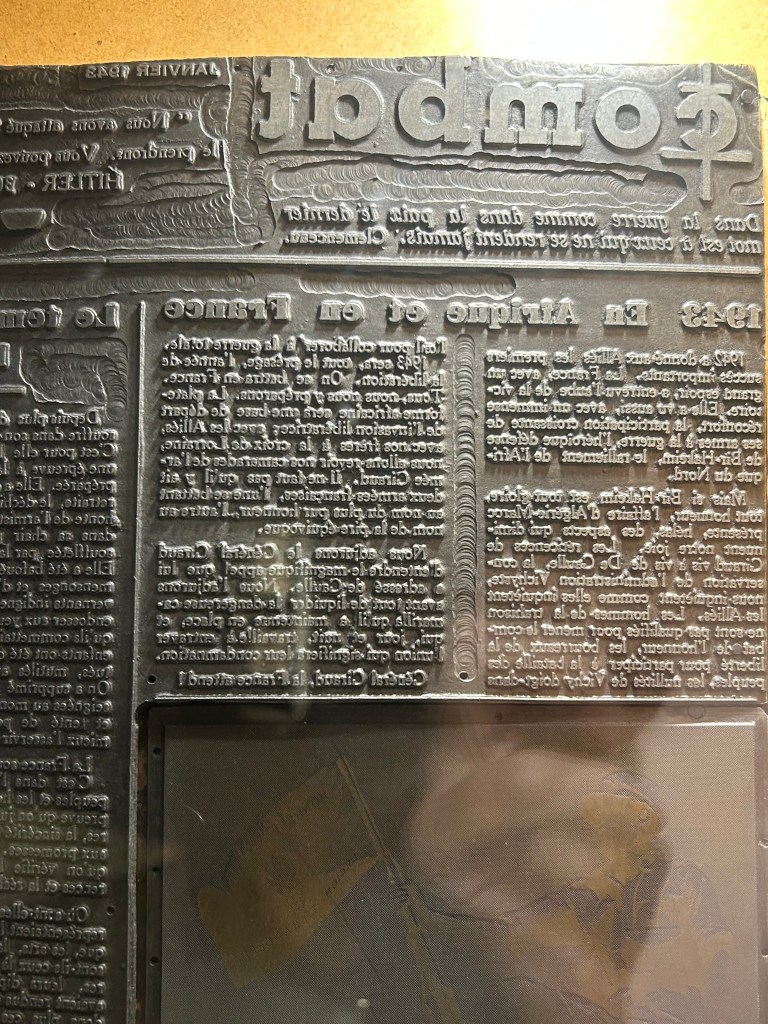

The press helps to make the visual form of the photograph legible. For example, the underground newspaper published daily by Reynoard’s résistance group, titled Combat, also is on display. The tone of the newspaper is captured in the masthead: the C of Combat is intersected by a crucifix and the sight lines of a gun. The citation below the masthead is from Clémenceau: “In war as in peace, the last word belongs to those who never surrender” (Dans la guerre comme dans la paix le dernier mot est à ceux qui me se rendent jamais). That is, whether in times of conflict or calm, those who refuse to give in, who persist and never give up, have the last word. Words matter. Headlines defiantly read “We must say: NO,” “We continue,” “In north Africa as in France the only one: DE GAULLE,” “Towards Victory.”

The newspaper, in sum, speaks loudly for members of the Résistance during years of intense pressure from the Vichy government to conform and cooperate with the Nazis. While its strength and power is belied by the fragility of the yellowed and torn pages, a lithographic block and printing press on display nearby make its criticality (and tangibility) as a touchstone for the maquis that much more literal.

Why does any of this visual thinking about courage matter today? This is not an easy question to answer; I began to do so for this post, then left off because the question raises many others. Why do we speak of lapses of courage rather than failures of courage? Why do some people never act with courage? How is fear being mobilized by the US and Israel to defeat courage?

But I do want to leave you with one thought about the relevance of the Musée. One of the common responses to any critical writing about the genocide in Palestine is: go read a book. By now, many of us have read many books. What I would like to see are the critics who stand with Israel following their own rhetoric––the rhetoric that knowledge of Palestine and the genocide lies only in their hands (and the troubling insinuation that that knowledge is power)––by reading about the maquis and dwelling on the lessons in courage and the ways it matters to human rights to be learned at the Musée. The continuing terror and horror of the genocide gives us no reason to be optimistic, nor does the March Haaretz poll of Israelis indicating that the majority support the genocide, but maybe they’ll learn, at the least, that they won’t have the last word. For the rest of us, the Musée sustains a glimmer of hope.

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation de l’Isère

14 Rue Herbert, 38000

Grenoble, France

Books linked to the US Library of Congress database

A. J. Liebling: World War II Writings (LOA #181) by Pete Hamill (Editor)

And There Was Light: The Autobiography of a Blind Hero in the French Resistance by Jacques Lusseyran; Elizabeth R. Cameron (Translator)

A Bag of Marbles by Joseph Joffo

The Cost of Courage by Charles Kaiser

Femmes dans la guerre : témoignages, 1939-1945 by Hélène Gestern

French Heroines, 1940-1945 by Monique Saigal

Images d’une certaine France : affiches 1939-1945 by Stéphane Marchetti ; préface d’Alain Weill

J’ai voulu porter l’étoile jaune : journal de Françoise Siefridt, chrétienne et résistante by Françoise Siefridt ; préface de Jacques Duquesne ; postface de Cédric Gruat

Madame Fourcade’s Secret War by Lynne Olson

Mille visages, un seul combat: les femmes dans la Résistance : témoignages by Simone Bertrand

The Resistance 1940 by Charles B. Potter (Editor)

The Spiral Shell by Sandell Morse

NB: For the original French texts translated in this post, see the images. The Trilling article cited in this post is by Daniel Trilling, “Is this Fascism?” London Review of Books 47, no. 10 (June 2025).

[1]Portraits from left to right: 1)Mélinée Manouchian (1913–1989). Survivor of the Armenian genocide, immigrated as an orphan to Smyrna, Corinth, and in 1926 to Marseilles, where she met her future husband Missak Manouchian (also pictured in the mural). Résistante and active publisher and distributer of forbidden anti-fascist literature. 2) Jean Zay (1904–1944). Left-wing lawyer and Minister of Education from 1936 to 1939 (during which time he established the Musée d’Art Moderne, the Musée de l’Homme, the Musée des Arts et Traditions Populaires, and the Cannes Film Festival). He also was a Freemason. He was arrested in August 1940 by the French Vichy regime and in 1944, during a prison transfer, they assassinated him. Died at age 40. 3) Pierre Brossolette (1903–1944). Journalist and ardent socialist. Résistant leader of the Comité d’action socialiste (Socialist Action Committee). Helped to establish the National Council of the Résistance and was one of its major heroes. During an attempt to go to London in 1944 to meet with de Gaulle, he was captured by the German Gestapo. After severe torture he threw himself from his prison window to avoid revealing the crucial information that he possessed. Died at age 41. 4) Geneviève de Gaulle (1920–2002). Niece of Charles de Gaulle, résistante deported in 1944 to the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp (she was then 23 years old). She later became a human rights and anti-poverty activist and was president of ATD Fourth World from 1964 to 1998. 5) Germaine Tillion (1907–2008). A woman of letters and French ethnographer. Résistante member of the Groupe du musée de l’Homme (Group of the Museum of Man). Betrayed by the Nazi collaborator Robert Alesch, she was arrested on August 13, 1942 (she was then age 35), and later deported to the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. 6) Jean Moulin (1899–1943). Civil servant (prefect of Eure-et-Loir) who unified the main cells of the Résistance over the course of two years, in 1943 and 1944. He was arrested by the German Sicherheitsdienst (the secret Law and Order Services of the SS)on June 21, 1943 and was tortured to death by Klaus Barbie. Died at age 44. 7) Missak Manouchian (1909–1944). Poet and survivor of the Armenian genocide, immigrated to France from Lebanon in 1925. Leader of the Francs-tireurs et partisans – main-d'œuvre immigrée(FTP-MOI), a cell of resistance fighters who like him were immigrants, mostly Jews. He and twenty-two members were arrested and interrogated by Vichy police in 1944. In a show trial that began on February 17, after a 30-minute deliberation, the court reached the following verdict: all of the accused were condemned to death, with no possibility of appeal. Following their executions, the Germans created a poster with a red background featuring ten men with their names, photos, and alleged crimes. It became known as l'Affice Rouge. The Germans distributed thousands of copies of the poster around Paris to encourage Parisians to think of the partisans as criminal foreigners and “not French,” and to discourage resistance; instead, the red posters inspired citizens to more actions. Some marked the posters with phrases such as Morts pour la France! (They died for France.) Manouchian died for France at age 35. [2] They are: 1) The course of the conflict seen from Isére; 2) Joining the French Résistance; 3) 1942, STO and Italian occupation; 4) Résistance groups; 5) The position of Jews in Grenoble and Isére between 1939 and 1944; 6) Autumn 1943 Résistance and counter-insurgency; 7) Deportations; 8) The Liberation of France.