The late 1970s and 80s found the painter Lin Fengmian 林風眠 (1900–1991) in Hong Kong, re-painting pictures that he had been forced to toss down the toilet during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), along with paintings depicting human suffering that were destroyed by the Japanese military in the 1930s. His act was one of restoration (bujiu 補救, in the artist’s words). He worked to remake the pictures as things of care. He dreamed up new authenticities. Yet he also intended to fold the paintings back into time, to take these pictures lost to crisis––by definition, moments wrenched from the flow of time––and return them to life. My new research project explores the temporal fluidity embodied in Lin Fengmian’s act of restoration. It asks how pictures from moments out of time were brought back into that flow through Lin’s idiosyncratic “Cubist” fractured styles of rendering––restoring––the human body as if visible from different times and perspectives all at once, drawing on Einstein’s and ancient Chinese temporal-cosmological thinking.

One of those lost paintings is titled Humanity’s Pain 人類之痛苦 (1929). It lives today as a black and white photograph. Across the stretched-out composition there are three contorted, naked torsos, heads thrown back, anguished, and possibly, dismembered. To the left there are rib cages, maybe skeletons. The pictorial surface fractures so that it appears flat in some places and possesses a spatial dimensionality in others, and it leaves the sense that there is more to be seen. The painting was made after the Shanghai Massacre or “April 12 Incident” 四一二事件 of 1927, when right-leaning Nationalists 國民黨 arrested, tortured, and executed hundreds of Communists and left-leaning Nationalists, union leaders and workers, triggering several years of anti-Communist violence. The loss of the original painting imparts a finality to the loss of human life pictured in it.

During the pandemic lockdown it was a picture I returned to repeatedly. I find its traces beautiful and able to convey real pain, perhaps even more so because the photographic medium deepens the blacks and whites. In a more prosaic sense, its interest was that it was something I could see as if in the flesh; I was estranged from the paintings and things I usually study in person, mostly in China, and in the United States and Europe as well. This photograph was the picture.

For the artist, though, even after it was destroyed, the picture always was more than a photograph. The oil pigments that Lin used to create it in 1929 can be considered part of his performance of making art. That performance was bodily, muscular, active. If we think about it from the perspective of Chinese brush-and-ink practice with which Lin was intimately familiar, the painting was held within the sinews and organs of the body and was inseparable from the act of picking up the brush. To make a “copy” of a painting, to restore it, would be to move the arm and hand in the original gesture, to perform a physical memory.

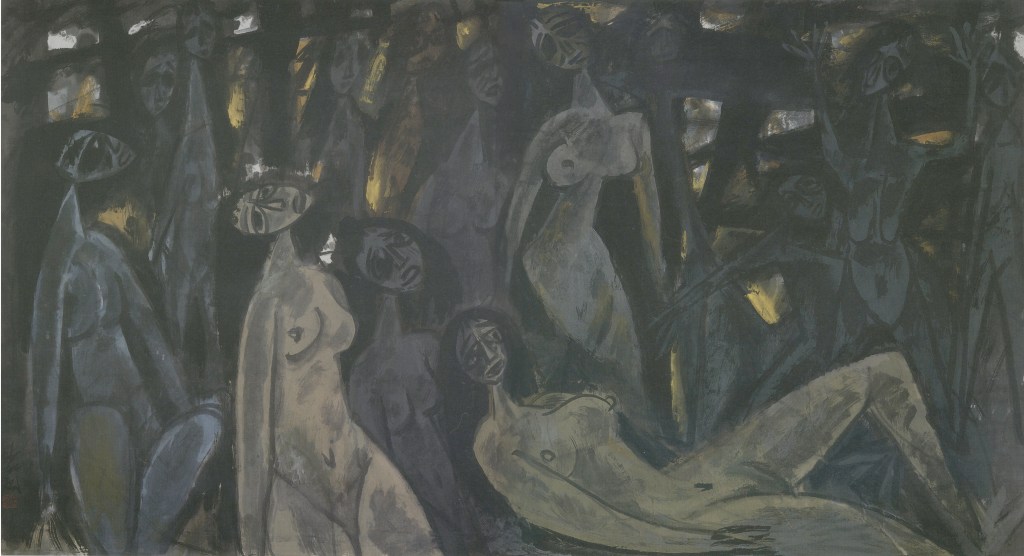

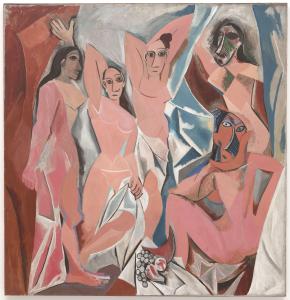

Yet, Lin’s restoration of the painting roughly fifty years later ended up looking similar but also quite different from the original. It’s clear that he wasn’t after “copying.” The new painting still features the same three figures, rendered in lighter yellowish green-grey colours, now more clearly standing or prone among a group of spectral figures rendered in lavender-greys and wet blacks. Their necks are conical below faces like masks, in the shape of pointed ovals, flat except for large eyes, triangular noses, and quick slashes of the brush as mouths. The lumpiness and softness of the earlier painted torsos has disappeared, replaced by heavy gestural brushwork and geometric planes. If anything, the figures recall the masked women in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) which Lin might have encountered during his years as a student in France and Germany, 1919 to 1926. The repetition of the figures also recalls Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (1912), a distillation of movement and time onto a flatly painted surface.

The questions about what restoration means for the artist, then, are driving my research. What was the temporal valence of Lin’s newly imagined cubist style that seems to draw as much from Picasso and Duchamp as it does from Chinese art practices? How do we engage fully, bodily, with traces of loss from crises outside of time? Can restoration reduce pain? How to write about a work of art that occupies different and multiple times in a way that respects its heterochronicity?

So equally, I am interested in the way that the original painting––a picture that is visual but in some profound senses invisible––is returned to visibility and to time through the way I or anyone else encounters it and writes or talks about it. For any of us to have a meaningful dialogue about the lost painting (and the restored painting), we rely on the practice of art historians of saying what we see, showing (not telling) each other what we encounter. This is not a mechanical drafting of a social history of social art, an imposition of Western art historical thinking and structure on any artwork, even ones that may resist it, as this one does, in multiple ways. Writing is a form of encounter with art. There’s an obvious ethics to the practice of deep visual engagement, and, by engaging with humanity’s pain in Lin’s painting within the context of the terrible human suffering we see everyday in Gaza, an urgency to it as well.

To be sure, writing about Lin’s paintings is not going to save a life. It won’t comfort those in tears or prevent the people who caused the tears from blaming others for failing to understand. It won’t make much––any––difference to politicians and their rhetoric. The Biden administration’s unwavering, billion-dollar support of the Netanyahu government is not going to change no matter what you or I do, although it does underscore the problem of finding perspective, and how we see or fail to see humanity’s pain. But I think I am right in insisting that Lin’s depictions of suffering and the questions they pose of us are relevant to navigating the crisis in Palestine now. However modestly, the artist’s loss and act of restoration can help us stumble our way through this painful moment of blindness and atrocity, and the almost complete breakdown of history and human care for others.

For the Medecins sans Frontieres April 4 briefing on Gaza, click here.

For the US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s statement in a hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee on April 9 that “there is no evidence of genocide being carried out in Gaza,” see the PBS report here.

Lin Fengmian 林風眠, Renlei zhi tongku 人類之痛苦 [Humanity’s Pain]. 1929. Dimensions unknown. Black and white photograph of oil painting destroyed in wartime.

Lin Fengmian 林風眠, Tongku 痛苦 [Pain]. 1980s. Colour and ink painting; 83.5 x 151.8 cm. Private collection.

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907. Oil on canvas; 244 x 234 cm. MoMA.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912. Oil on canvas; 147 x 89.2 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art.